The inability to say thank you

March 21, 2017

English is one of the most difficult languages to learn, not only because many of the sounds are harsh and contradictory, but also because half the letters disappear when the words leave your mouth.

However, for me, the hardest word to say was never otorhinolaryngologist or anemone or supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, but thank you.

It was probably some horrible memory that I’ve repressed from my childhood, but for whatever reason, my three biggest fears have always been drowning, those millipede things that crawl out of the drain, and most of all, narcissism.

Accepting a compliment always felt conceited and something about thinking you’re better than you are, or at least having people think you think you’re better than you are, absolutely terrifies me.

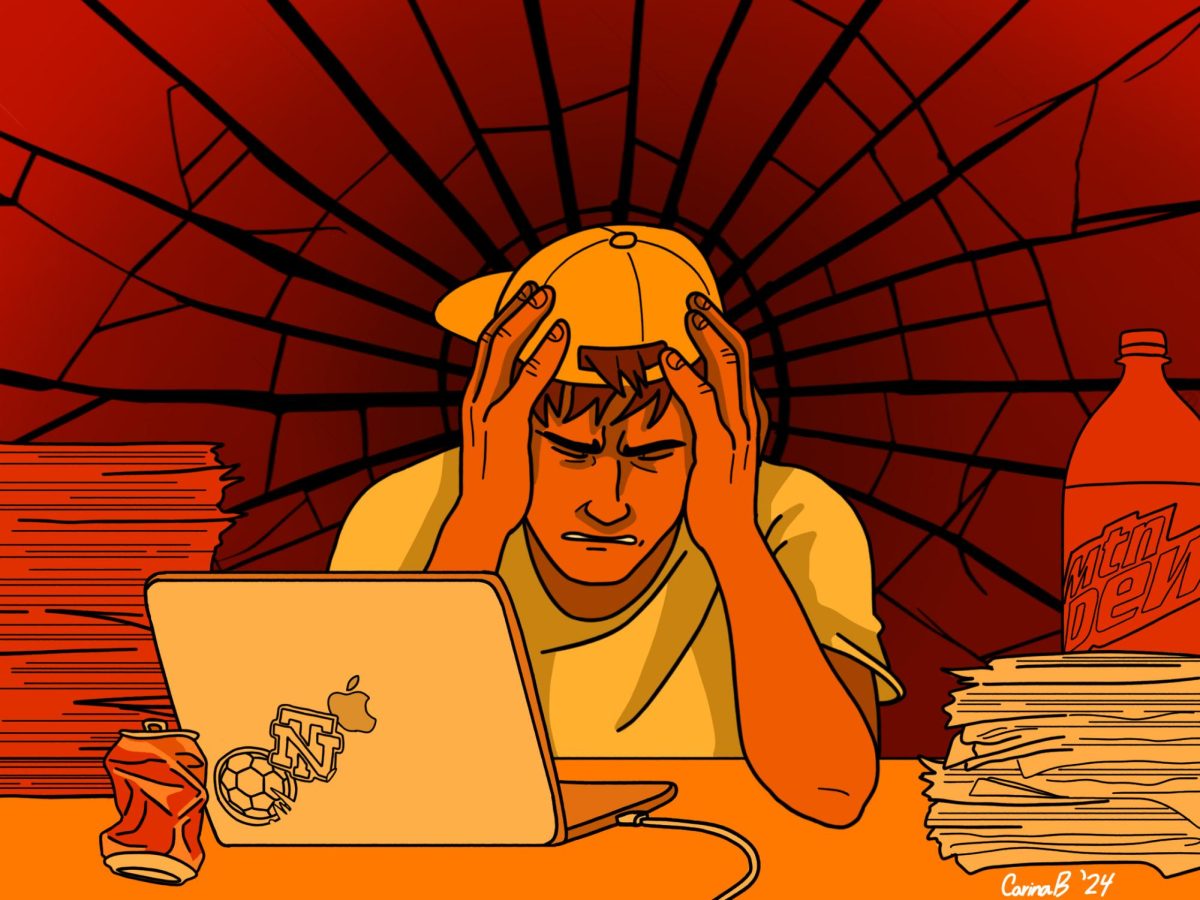

I’m not exactly sure why this is. It could be because of social pressures to act courteous and meek. It could be because self deprecation is like 75% of all the humor I have. It could be because I’m afraid of failure.

Whatever it is, getting compliments always makes me wildly uncomfortable.

It’s odd, because I never felt like I was significantly lacking in confidence. At least, not to a greater extent than any other teenager that’s ever existed.

As far as I know, it’s not an inability to comprehend my actions as it is an inability to accept them from other people. But I don’t really think about it much anymore, but I feel like it’s more of a lifestyle choice than a real issue.

I have, for as long as I can remember, played the contrarian. This rings true for the television I watch, for the music I listen to, and most of all for anything positive that is ever said about me. I’m a “no-I’m-not” robot.

“That drawing’s really cool.”

“No it’s not.”

“Your essay’s really good.”

“No it’s not.”

“Your shoes are a nice shade of blue.”

“No they’re not.”

I’ve never had a problem setting reasonable goals for myself, so it seems like I can reasonably assess my skill level at certain things, but when it comes to proclaiming it out loud, it becomes an issue.

I’m certainly better than I used to be, at least I hope so, but saying thank you still sometimes feels like pulling a tennis ball out of my throat.

I just feel like saying you’re good at something is such a bold statement, even if it’s the tiniest thing. What does that even mean? People told me I was good at drawing when I was little.

I was not good at drawing. My peoples’ heads looked like uneven watermelons; their hands were sticks and they had at least 8 fingers per hand that went all the way around the wrists.

But the complements weren’t ingenuine. People genuinely thought my watermelon-headed, stick-armed, ceiling-fan-handed doodles were good–for a 4 year old.

So there are different standards for 4 year olds. Makes sense, they’re little, but there are standards for 17 year olds too, and 25 year olds, and 40 year olds and 80 year olds.

So are we ever objectively good, or do all of our talents hang in a chasm of subjectivity until the end of time?

I suppose talent is a sort of Democratic process. If enough people agree on it, it must be true. How else would the three grey canvases I saw at the Art Institute last year get there?

They certainly weren’t selected for their technical precision and attention to detail. But then again, everyone thought Aristotle was crazy when he said the Earth wasn’t flat, but he turned out to have a pretty good point.

But whether or not there is an objective talent, whether or not I’ve ever been truly talented at anything in my life, I feel the consistent need to thrust my humility onto others, even if they’re just trying to say something nice.

It’s so stupid because I don’t think anyone has ever given a compliment only to denounce the person they gave it to as a narcissist. In fact, giving a compliment usually feels good.

That’s where the downside of this is: when I think about it, immediately snapping “no I’m not” to any complement is basically calling someone stupid for just being kind. And no one deserves to feel stupid.