Various pressures prompt Asian American students to change names

Changing names is more common than it seems

People change their first name for a variety of reasons, but usually they share a myriad of common ones.

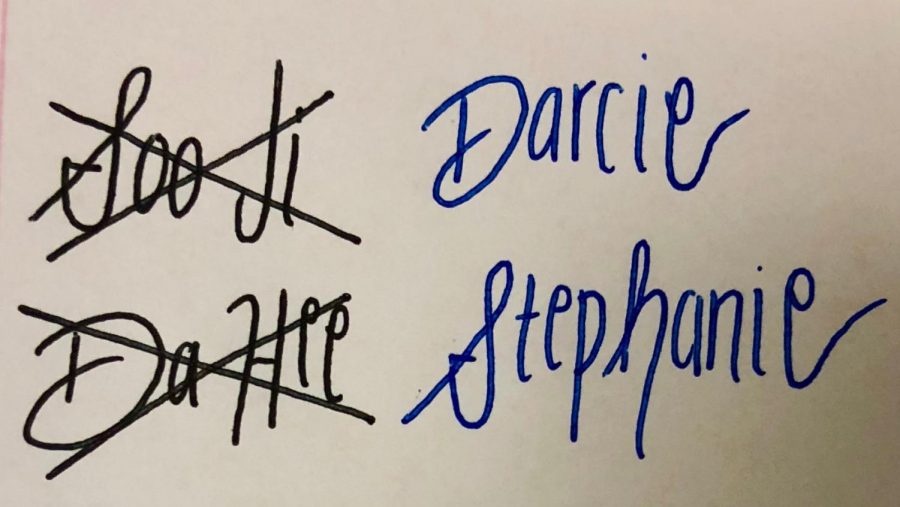

In my case, no one has ever called me anything other than Darcie aside from my grandparents who live in Korea. It’s the name I write at the top of my assignments and the name I turn my head to. I’m the first born child to first generation immigrants, and my parents weren’t cognizant that Korean Americans are often given an American first name and a Korean middle name. My passport was also under the name Soo Ji Kim, and sure, it irked me a little, but it was never cause for any major concern.

It wasn’t until I took Driver’s Ed and the teacher insisted on calling me by my legal name Soo Ji, which she pronounced “Suh Geeeeee?” raising her voice questioningly at the end, that I first became uncomfortably aware of the conflict regarding my name.

I went to court for the first time sophomore year. I picked out my nicest pair of pants and a pastel pink blouse the night before, determined to seem poised for my first official court date. The judge called my name and I slowly stood up, feeling my parents’ reassuring presence behind me. I wiped my sweaty palms on my pants before looking up and saying in a firm voice, “I would like to legally change my name.”

And in my case, the name on my birth certificate is Stephanie Kim. But two years ago, this wasn’t the case.

Walking into a classroom and seeing a sub sitting at the front is usually cause for celebration for most students. It’s hello to a quiet, relaxed work period, and your heart does a little happy dance.

Mine never danced, though. Usually, it sank with dread, anticipating the inevitable mispronunciation of my name and that the subsequent feelings of shame and ostracization.

“D-Okay, sorry if I butcher this. Da? Da Kim? Kim?”

Another one bites the dust, I’d usually think as my mouth puckered into a sour twist and my hand raised with an obvious reluctance. “Here,” I’d cringe as kindly as my consciousness can muster.

“Did I get that right? Da? Day-hiii? Dehe Kim?”

“Oh, yeah, yes,” I’d chirp quickly. “That’s correct.”

The sub will usually smile at her apparent triumph and call out the rest of roll call, which, of course, goes without a hitch now that my blip of a name is out of the way.

These experiences are a part of a larger story of a community of people in America whose names have never truly been a comfort, but a conundrum.

Issues with pronunciation arise too often, leading people with such names to feel damagingly different or too outlandish compared to their friends and family.

“Whenever a substitute or new teacher takes attendance, there will always be that awkward process of pausing, trying to pronounce my name, my feeble attempt at mentioning I go by Skye, and some will go the extra mile and ask, ‘How do you really pronounce it?’ With my more English-friendly name I just feel as though I actually fit in,” said senior Skye Ko.

Senior Brandon Lee shared a similar reason for changing his name from Sangmin to Brandon, “When people butchered my name like they did, I suppose it made me feel foreign. At the time, I was in a state of mind where I didn’t like feeling different from my mostly white, family-has-been-in-America-for-at-least-three-generations peers.”

For New Trier alum Julia Yang, the name Julia was given to her by a disgruntled teacher. Yang’s given name is Guangmei, an homage to her Chinese heritage and a name thoughtfully chosen by her parents. And yet, her kindergarten teacher wrinkled her nose while looking at the attendance sheet on the first day of school and announced that it would be too difficult to pronounce the name, thus telling her that she would go by Julia.

Changing one’s name to something allegedly easier to pronounce often succeeds in eliminating the discomfort associated with the original name. But why is there discomfort with unique names to begin with? Is it that our society makes it easier to feel accepted after changing a “foreign” name to a Western one?

Depending on location, a Western name might sometimes not even be valued at all. “When I go to Korea, sometimes I’m teased about changing my name,” said Lee. “My grandfather will say that it was unpatriotic of me to do so, but then I remind him that I’m not even a Korean citizen anymore.”

Pronunciation is hardly the only reason that pushes someone to change their name. For Ko, the strain of juggling two separate and distinct names became a lot to bear, mentally and emotionally.

“At home I was ‘Haneul,’ but at school I was ‘Huh-nule.’ Though it may sound exaggerated, even I ended up becoming confused as to who I was,” explained Ko. “In middle school, I resolved to change my name, at least amongst everyone who knew me, to the literal English translation, Skye.”

A new name can also come with a learning curve in terms of both the person them self and their peers growing accustomed to it. “My friends were surprised, and a lot of them asked if they could keep calling them by my old name,” explained Lee. “Some of my oldest friends still call me ‘Sangmin,’ but mostly, I’m ‘Brandon’ now.”

Though it appears that there is a lot of societal pressure to adopt a Western name, all who do stress that the choice is ultimately theirs to make.