In late September, the Glencoe Historical Society removed the name of former resident Sherman Booth from the title of Booth Cottage, a historical Frank Lloyd Wright-designed cottage in the Ravine Bluffs neighborhood. While assembling an exhibit on the history of Blacks in Glencoe, the Society uncovered extensive records of actions Booth took to push Black residents out of their homes in the early 20th century. In light of this new information, we decided to take a look at the factors that define the racial makeup of the North Shore today.

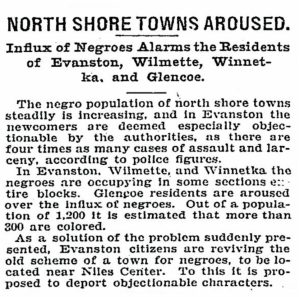

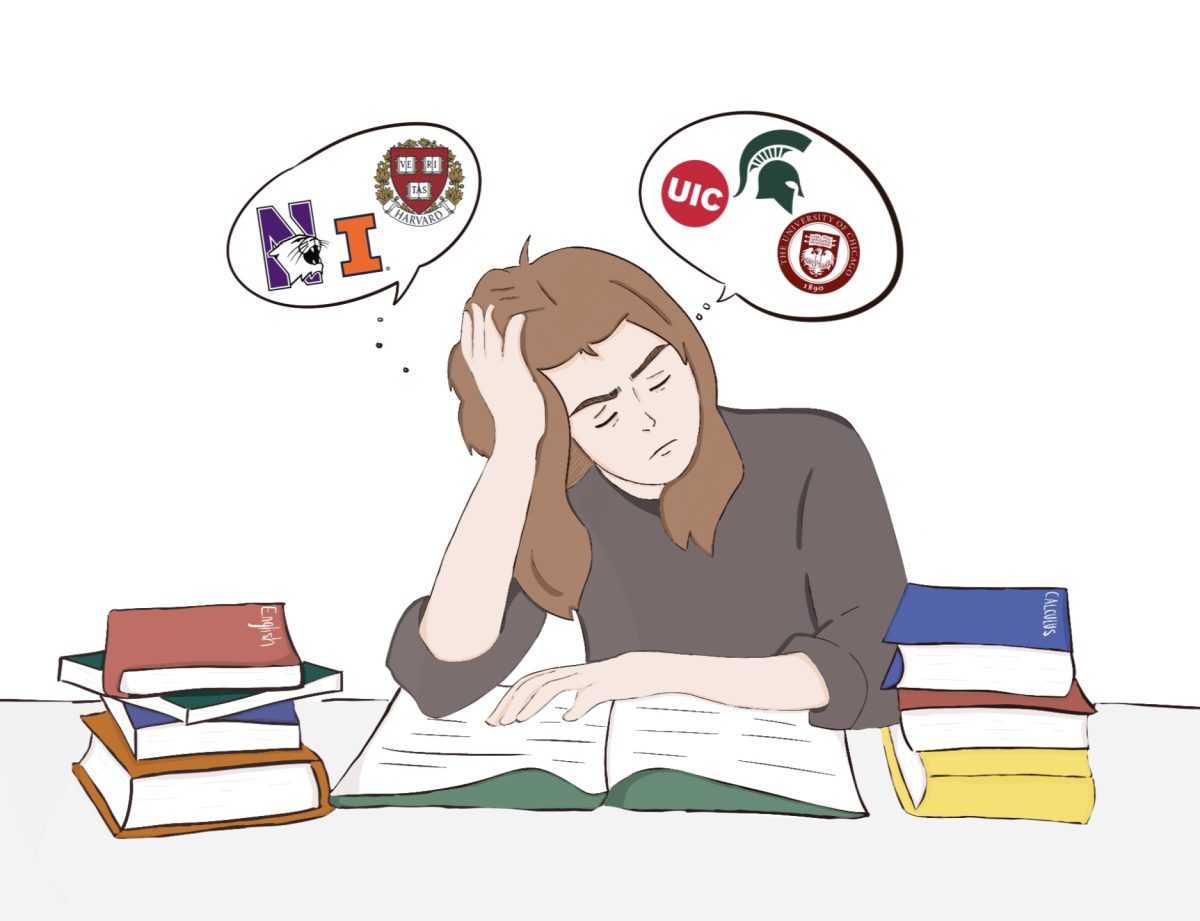

Living in and interacting with the North Shore induces a simple observation: it’s not very diverse. The population of Glencoe, for example, is 92.2% white. The next two largest racial groups are Asians, comprising 2.2%, and Blacks, comprising 2.1%. That trend is consistent through the rest of New Trier Township; Winnetka, Kenilworth, and Wilmette are 90.7%, 84.2%, and 80.1% white, respectively, per the 2020 census. For comparison, Blacks constitute 13.7% of the total U.S. population. The patterns of racial homogeneity in the North Shore are a product of racism and discriminatory policy in the early days of our township.

The Roots of Housing Inequity

The history of minority groups on the North Shore is one that varies by community, and Glencoe stands out as a unique historical case. From its incorporation in 1869, in the middle of the Reconstruction era, real estate agents in Glencoe actively incentivized Black Chicagoans to move north to the suburbs. Newspapers like “The Conservator” printed out ads from businessmen like Ira Brown and William Ambrose, drawing buyers in with relatively cheap land. The town hosted picnics for prospective Black home buyers making the journey from the city by train. For those with children, Central School was also the only integrated school in the area. As a result of the relatively relaxed racial attitudes in the town, estimates from the Glencoe Historical Society put the Black population of Glencoe at the time at 10%. A “Chicago Tribune” article from 1904 estimated that 300 of Glencoe’s then 1,200 residents were Black.

Early community leaders with a history of supporting the Black cause helped shape Glencoe’s identity as a standout in Black rights. One resident, Charles H. Howard, was an incorporator of Howard University (a historically Black university), a Union Civil War general with 67 battles under his belt, and an assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Howard was a village trustee from 1884-85, a village president from 1891-92, and became head of the Central School board in 1893.

But we noticed a sudden shift in attitudes amid the 1919 race riots in Chicago, part of a larger wave of racially-fueled violence that swept across more than three-dozen American cities that summer. Suddenly, residents felt threatened by their minority neighbors, fearing violent retribution. A letter from a citizen claimed to have evidence that “colored people” were gathering arms and munitions, seeking an investigation from Washington. Later in 1930, the St. Paul A.M.E. Church, a historically Black church that served as a community center for the population, was attacked by arsonists Robert Clavey and Lawrence Diettrich. Similar to many hate crimes in the era, the two men faced no jail time. Clavey later had a road named after him in Highland Park.

The Glencoe Homes Association was established, not coincidentally, on July 31, 1919, at the back end of the riots in the city. Known colloquially as “The Syndicate,” its self-proclaimed mission was to maintain “civic duty and [protect] their own property, for had they not done so, the Village of Glencoe would have been overwhelmed with the negro colonization and would have ceased to be a desirable residential district for white persons,” according to the Glencoe Historical Society.

Sherman Booth, a co-founder of The Syndicate, later went on to become a founder of the Glencoe Park District.

The Syndicate’s Influence On Housing

The Syndicate, supported by individual contributions of at least $1,000 ($19,000 today), used its collective funds to purchase Black homes throughout Glencoe. When owners refused to sell, The Syndicate employed various tricks. For example, it might contract a third-party to make an offer posed as a nonaffiliated buyer who would then transfer the property to The Syndicate. Or, holdouts were offered finance in the form of a home-improvement mortgage. As homeowners fell behind on these mortgages, The Syndicate swooped in, seizing the property on terms of foreclosure. When The Syndicate resold its amassed properties, it attached racially restrictive covenants that prohibited owners of the property from selling to Blacks.

This influence began to rear its ugly head during the mid-1920s. In this time, The Syndicate bolstered its influence through the arm of the public government, flexing the muscles of eminent domain. Eminent domain, the right of an authoritative body to acquire private land for public use with just compensation, is usually reserved for government entities. In the state of Illinois, however, that power is bestowed on park districts, too.

With Booth in positions of power at both organizations, efforts to push minorities out of Glencoe could be coordinated and executed with cutthroat efficiency. During the ‘20’s and into the early ‘30s, the period that Booth operated The Syndicate, the population of Black residents in Glencoe plummeted from 10% to 4.9%.

“The power of government is particularly important because it includes eminent domain,” Peggy Hamil, a director at the Glencoe Historical Society, said. “If the government says they need your land, you may not refuse them. If a private individual wants to buy your property, you can say no. But through the power of eminent domain, many more parcels of land belonging to Blacks and Italians were purchased.”

In Glencoe, each school has a local park attached to it. So, when the township was building South School, it planned to include a park which would require space nearby the school, space that was occupied by houses. Houses along Monroe, Madison, and Vernon avenues were all seized by the local government for the park. Most of the land bought out was not used at all by the Park District and instead left undeveloped.

As late as the 1960s, Glencoe homeowners discovered they were unable to sell their homes to Black buyers due to Booth-era restrictive covenants. It’s important to note that after the ‘60s, the Glencoe Park District did not engage in any racial housing exclusion or prejudice because of the Fair Housing Act, passed in 1968, outlawed racist housing practices.

Lasting Effects

Despite this, the population demographics haven’t returned to what they once were. In the time that Blacks were pushed out of and subsequently legally barred from purchasing homes on the North Shore, home prices shot up. The barriers now are financial ones. The average North Shore house is $620K.

Glencoe was an outlier, though. For other North Shore communities like Wilmette, there was little initial welcome for Black populations. Like most rich, predominantly white neighborhoods, racism was ever present and even normalized. For instance, a fair poster from 1913 used racial slurs to advertise a game in which participants used a ball to knock over pins painted to represent Black children. Black residents and employees in Wilmette were threatened with death if they did not leave the area. The Women’s Club of Wilmette held minstrel shows in which cast donned blackface. And letters to the Village Board indicate evidence of real estate agents pushing for wider cooperation to interdict sale to Blacks. The Wilmette Historical Society has an excellent online collection documenting this past.

And yet, Oak Park, a community also near Chicago and also relatively wealthy, has managed to retain a 20% Black population. The difference?

“The village government of Oak Park had a Fair Housing office and always had a facility and staff for people to come in and work with them to try and make sure that if it’s possible to sell to people of different ethnicities and backgrounds,” said Hamil.

Unfortunately, due to a combination of initial push back and segregation practices, then an array of economic factors, the North Shore doesn’t have a diverse population, which brings a myriad of negative impacts, including a lack of access to interact with people of diverse backgrounds. However, New Trier is working to provide these opportunities, through curriculum and suggestions by equity liaisons. One liaison and teacher at New Trier, Alex Zilka, talks about the road ahead and the effort that the school is putting forward.

“I think that we as a school make efforts to try to give students opportunities to learn about other cultures and to build empathy, even if we don’t necessarily have a very diverse school. Is it the same as living in a diverse community? It’s not, but we’re trying to bridge that, move the needle and bridge that gap as much as we possibly can.”

Cynthia Fey

Dec 18, 2024 at 9:19 am

Thank you so much for your research and commitment to this important part of our local history, especially within our current climate of erasure and silencing!

Alan Hoffman

Dec 16, 2024 at 4:57 pm

I found this article to be very informative. I grew up in Glencoe starting in 1949. During my time at North School and then Central School and ultimate at New Trier, my racial consciousness grew. We were taught that Glencoe ( I believe the original name of Glencoe was Taylorsport) was a stop on the underground railroad and a least some of African Americans living in Glencoe were descedants of the original “passengers” on that Underground Railroad. At Central School there were a limited number of Aftican American students, perhaps 5 or 6 per grade. As I remember the neighborhood that all or nearly all lived in was in southern part of Glencoe.

One question I have is: Was Glencoe (Taylorsport) actually a stop on the Underground Railroad.? I think I recall seeing signs that Glencoe was incorporated in 1868, three years after the end of Civil War and likely the end of Underground Railroad. I be curious to know more of that period’s history.

I’ve lived most of my adult life in Minnesota. I’ve learned a lot of the racial history and real estate convenants in Minnesota.

Thanks for sharing the information in article