Starting this year, New Trier High School has implemented a new set of guidelines around the use of AI for schoolwork, with a statement summarizing the district’s philosophy around AI included in common syllabus language that all teachers received at the start of the school year.

According to Melissa Dudic, the new director of curriculum and instruction, New Trier supports AI in the classroom only when used responsibly and cleared by a teacher first—it should never replace the development of skills integral to a course. It’s the teacher’s responsibility to evaluate what’s best for their students within the preexisting set of rules and make the expectations clear to them.

The guidelines were finalized by a group of administrators in a series of workshops this past summer, but input came from a wider range of staff members, including department chairs and building administrators.

“AI is just everywhere,” Melissa Dudic, the new director of curriculum and instruction, said. “We have to adapt to that. I think the most important thing that we can do for our organization and for our students is to make sure we’re clear in our expectations about when to use it and that we can help give students the tools to use it appropriately, too.”

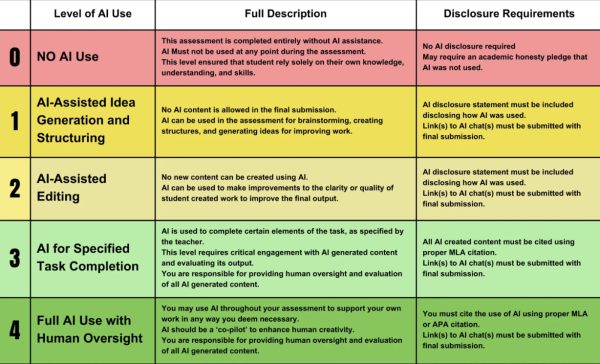

Outside of the policy, teachers have some freedom in how they choose to enforce these new rules. Many kicked off the school year by showing their classes a chart outlining which degrees of AI use are acceptable in various situations. Red signifies absolutely no AI under any circumstances, while dark green gives students flexibility to use it if they cite it in their work and communicate clearly with their teachers.

Of course, levels of acceptance of AI vary across departments, with less tolerance in the humanities.

“I would say in English, a lot of times, you’re going to see teachers saying ‘not for this,’ because the nature of our discipline is critical thinking.” Edward Zwirner, New Trier’s English Department chair, said. “It’s building those abilities to think independently. So if AI really interferes with that, you’re going to see a very limited use [of AI] in this discipline.”

Zwirner went on to explain an MIT study that measured the neurological responses of students using brain caps while they wrote an essay each, with the three groups being allowed varying degrees of help from technology. The results made it clear that the group using AI showed the least amount of brain development while being offered the same amount of time as the other two groups.

Zwirner does, however, see the potential benefits of AI in more scientific fields. It can be used by individuals who have already proven their mastery in their chosen area of study to help with things like data sets. Junior Kayla Ritchie has also seen the differences in how her humanities classes and her math and science classes have approached the topic of AI usage, stating that the latter haven’t brought it up at all.

Discussion surrounding AI exists outside of core classes as well, though.

“My debate teacher says AI can be helpful for gathering information or telling you sources that would be good for gathering information,” Ritchie said. “Of course, you have to fact check everything. But he thinks AI used for the purpose of writing is not as useful right now, and he can definitely tell when we’re using it to write.”

Because AI has been a long-standing problem for educators, teachers have gotten better at detecting its use in students’ writing. Ritchie said that several of her teachers say they can tell when one of their students uses AI for an assignment.

“It [AI] can, in some cases, be used as a tool, but also needs to be used carefully,” Dudic said. “That’s what teachers should be explicit about.”