A cornerstone of college admissions for decades, standardized tests like the SAT and ACT have come under intense scrutiny in recent years. During the pandemic, colleges widely adopted test-optional policies, and most continue to operate without requiring scores. Critics argue that these exams disadvantage low-income students—a concern with merit. Still, standardized testing remains one of the fairest and most objective components of the college admissions process.

Eliminating standardized testing is a shortsighted approach that exacerbates the very inequities it claims to address. I acknowledge that I may not be the best messenger for this, coming from a school district with both household incomes and standardized test scores well above the national averages. But in applying to college over the past year, I’ve come to see that standardized testing is one area where wealth plays a much smaller role compared to other parts of an application.

While there is a correlation between SAT/ACT scores and socioeconomic background, the same is true for academic performance. Free, high-quality test prep resources, such as Khan Academy, YouTube videos, and official College Board practice tests, have helped close the gap for many students without access to expensive tutors as well.

We also shouldn’t think of test scores in a vacuum. When test scores are deprioritized, greater emphasis is placed on other measures of an applicant where wealth confers a much greater advantage, like essays and extracurricular activities. Students in affluent schools like New Trier High School generally have access to better college counseling, professional editing for essays, and appealing extracurricular opportunities like internships or volunteer work. That’s not to mention legacy admissions, which disproportionately benefit wealthier students, or the phenomenon of grade inflation, an issue prevalent at wealthier schools.

All things considered, the SAT/ACT is just about the most level playing field of any of the main factors considered in a college application. Ultimately, it’s uniform for all students, regardless of their background. Everyone takes the same test, under the same conditions, and is graded by the same criteria—something that can’t be said for other components of an application.

By no means do I think that standardized testing is perfect, however. For example, the overuse of testing accommodations is particularly a problem at more affluent schools like New Trier and should be addressed. I’ve overheard peers and parents admit they sought testing accommodations—such as extended time—not out of necessity but simply to gain an edge. This practice undermines the system and disrespects those with legitimate needs for such accommodations, and addressing such loopholes is critical.

However, unlike grades, which can be subjective and vary widely between schools and even teachers, standardized tests provide students with a rare opportunity to stand out academically. A strong SAT or ACT score allows students from less wealthy schools to demonstrate their abilities. For high-achieving students in schools with less rigorous coursework or fewer AP classes, standardized tests offer a platform to demonstrate college readiness.

Some argue that tests like the SAT reflect test-taking skills more than intelligence itself, and while that may be true in some cases, intelligence is a nebulous term anyway. Does a single number truly capture a student’s ability? Of course not, but neither does reducing five months of work into a single letter on a transcript. All of these questions have merit but are not the sort of checkmate against standardized testing that some may think they are. The SAT, for all its flaws, provides a valuable benchmark nevertheless.

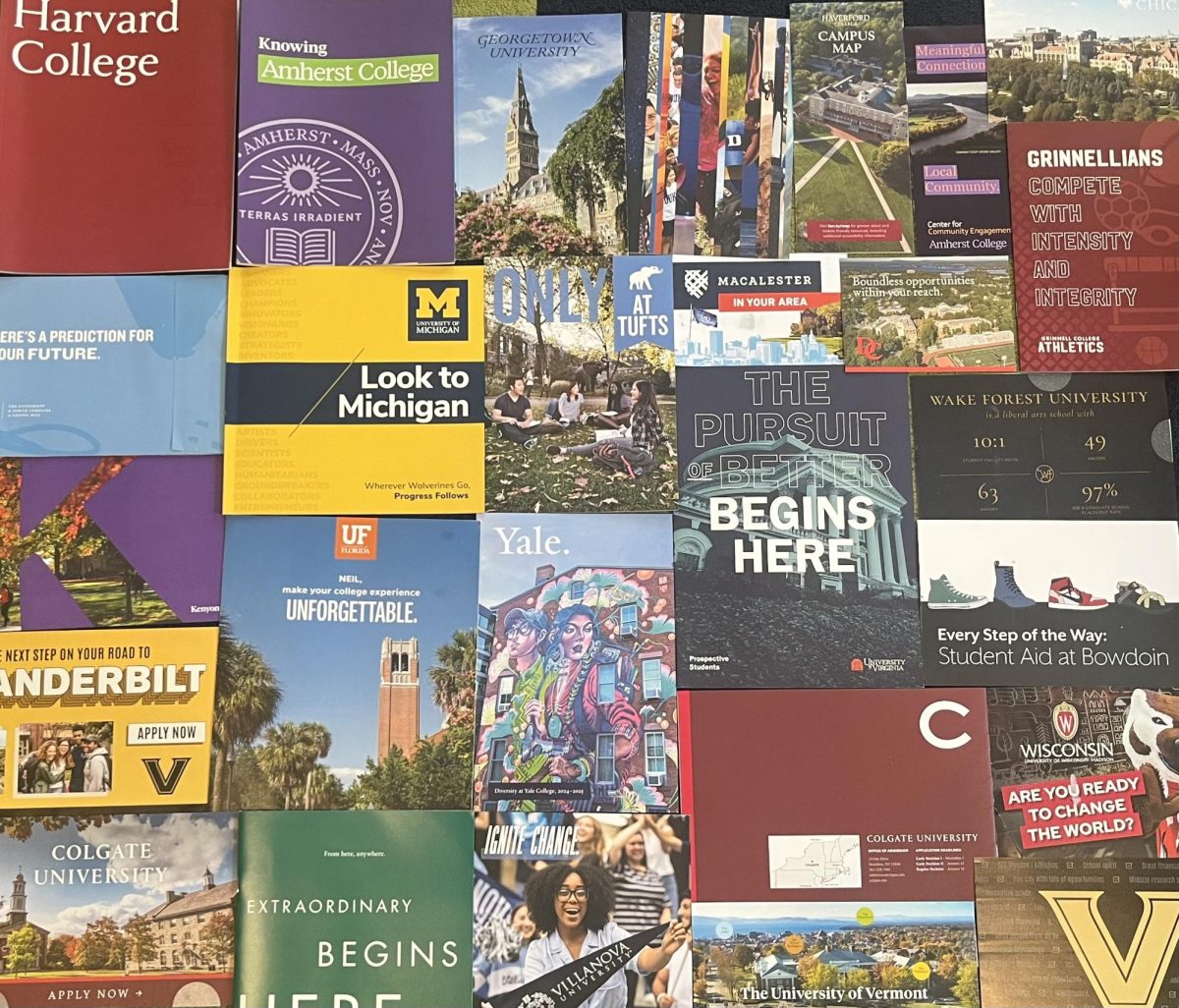

The rise of test-optional policies has made navigating the college admissions process, a difficult and stressful enough task, even more complicated. Further, in some instances, these policies even harm low-income students. A Dartmouth College-commissioned study found that there were many less-advantaged applicants who “should be submitting scores to identify themselves to Admissions, but do not under test-optional policies.” This is because scores are considered in the context of an applicant’s high school; many applicants have scores that are below Ivy League averages but are highly impressive in their context, for the same reason that a 35 on the ACT from a student at a low-income, rural Illinois school will stand out much more than one from New Trier. As a result, Dartmouth reinstated its testing requirement last year, joining a small but growing group of schools in returning to test score requirements.

Without test requirements, applications have inevitably increased, and acceptance rates at top schools have continued to drop precipitously. It’s hard to see who benefits from this. Colleges can only give so much time to each application, and while they likely don’t mind a lower acceptance rate, it’s no easier for them to handle. Students, on the other hand, enter an even more competitive college admissions landscape, one in which the influence of wealth may be inadvertently increased.

We should focus on making the standardized testing system fairer, whether by expanding access to test prep for lower-income students or targeting loopholes in testing accommodations. With the knee-jerk reaction of scrapping standardized tests, we risk increasing disparities while pretending this step is a solution to a larger socioeconomic issue. As debates about standardized testing continue, we should recognize that the SAT and ACT, as imperfect as they may be, are not the problem. Removing them is not a silver bullet but rather a myopic step in the wrong direction.