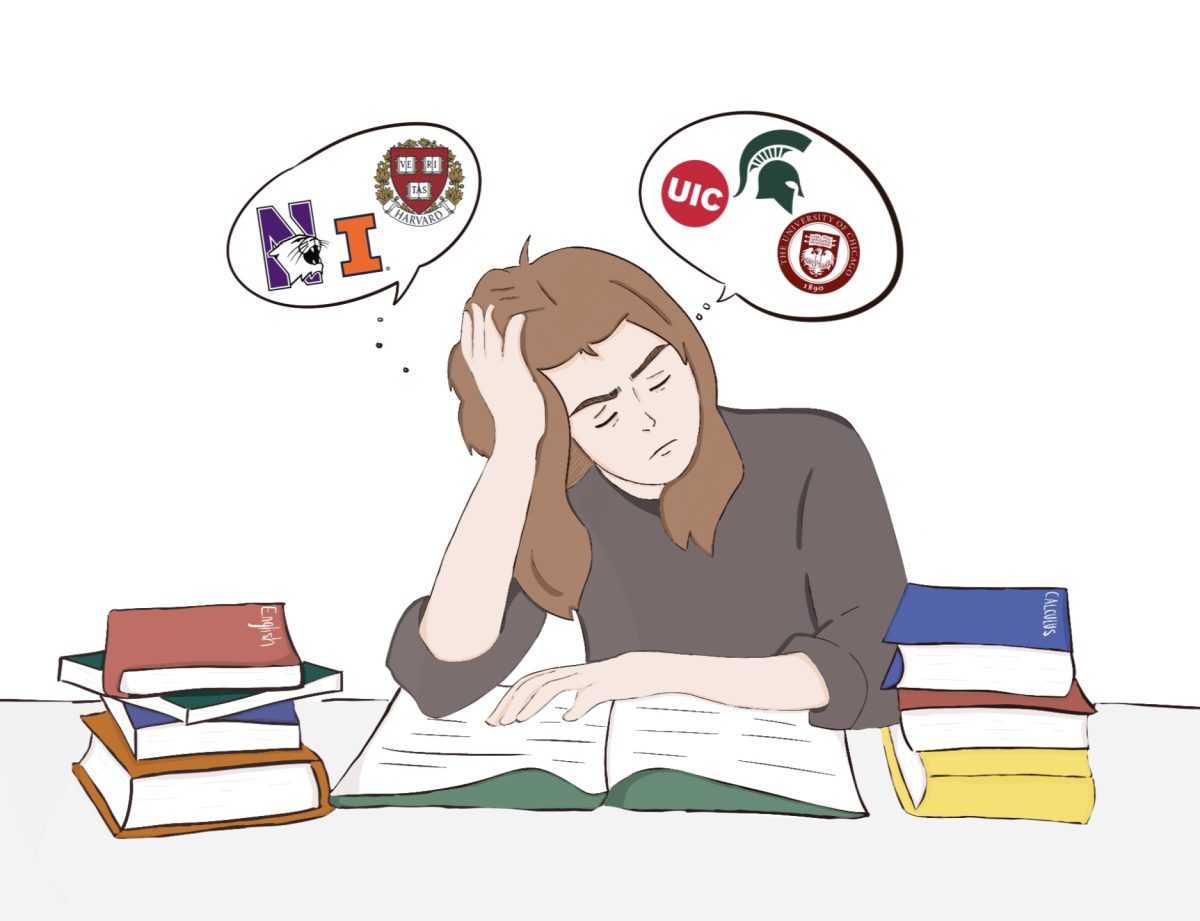

I am the first child in my family to attend New Trier. My parents went to small schools their whole lives with nothing like the academic options that I have. Neither of them could offer any advice on a high school like New Trier. I think many other older children will sympathize when I say that if you don’t know better, New Trier’s attitude towards education can be…frustrating.

Sometime in eighth grade, my mother and I arrived at the Northfield Campus to meet with an adviser about which classes I would take my freshman year. This was when I was first warned about the horror of level four classes. The adviser looked me in the eyes and told me that everyone who takes straight level four classes burns out and fails. Their grades drop, their GPAs are ruined, and their college applications suffer.

I’ll admit, this scared me a little. I was only 13, insecure, and easily influenced. Maybe New Trier really was where I’d meet my academic match. Plus, this was high school. My grades mattered. So I decided that in my worst class, math, I would drop down to level three.

Throughout high school, time and time again I was discouraged from pushing myself. I got straight As in my freshman year and was still warned not to take too many hard classes going forward. Especially in science and math classes my teachers told intimidating stories of the years to come. My biology teacher spent almost a full class period scaring us away from level four chemistry. She went on and on about how intense the class was. She recommended me for level three, and I, still trusting of authority, relented.

Halfway through my sophomore year, I decided that I was going to move up in chemistry, no matter what it took. I went to my teacher and explained my situation, to which she thoughtfully nodded and told me it was going to be incredibly difficult, if not impossible. Level four was “simply a different beast” that she didn’t believe I could handle. She said she wouldn’t feel comfortable recommending me for the class, and that if I decide to go through with it anyway, I should be prepared for my grade to drop.

After fighting the system every step of the way, I can report that level four chemistry is in fact fast-paced, challenging, and engaging. My previous A in level three chemistry has dropped to a low B, and it takes me real thought to understand the topics. A lot of the time, I’m a bit lost and have to ask the teacher for an explanation. I struggle with my homework, but after completing it, I feel confident with the work. I failed a test for the first time (a genuine fail, not a B. “F” was written in red ink on the paper). Granted, I didn’t study very well, but I learned from the experience and intend to prepare for the next test much more thoroughly.

This is how a high school course should look.

I don’t mean for this article to be solely my own personal experience and frustration with the school, nor do I mean to bash on New Trier’s education system. We are one of the highest rated high schools in the country, and clearly this way of learning works well for many people. Instead, I wish to draw attention to a major flaw in the mindsets of executives, teachers, and parents. The value of a high school education isn’t held in grades or a college resumé, but in understanding one’s learning preferences and exploring new topics as a teen. Our community does not consider the present. We constantly focus on what we are going to achieve in college, work, and beyond, before even graduating high school.

I believe that if students were taught to value education and pursue their academic interests for what they are in the moment, it would foster a society of intellectual teenagers who self-regulate their needs in order to better their learning environment. It’s a real tragedy that it is so challenging to push yourself at a school that prides itself on its academic excellence. Instead of scaring students with stories about challenging courses, teachers should encourage students to test themselves and try something difficult. When a student expresses an interest in taking more rigorous classes, it should be easy (in regards to the scheduling, I understand that moving up a level in any course takes studying and catching up outside of school), and the student should be praised for advocating for themself.

Of course, I am not implying that all students should take all level four classes. Those students are not better than others for doing so. Class levels should not be seen in terms of “better and worse,” but as different. I think that students should take classes that are engaging for them personally, and that fall in a different place for everyone. Taking classes that are too hard is incredibly time-consuming and exhausting, and no one should sacrifice their mental health, social life, or hobbies to overwork themselves in classes they don’t enjoy or benefit from. I also understand that it is not entirely the fault of the teacher. Historically, when students move up a class level, there can be some pushback later. A grade drop is more or less inevitable, and I’m aware that teachers are often scolded by unsuspecting parents and students, so I understand the hesitance to allow students to change levels halfway through the year.

What I am suggesting is a change in the way our community views education. I don’t want to be stuck in an environment where high school students are warned against taking the courses they want because it will harm something menial like a grade. I want to be able to learn in a way that brings me joy. I want to walk into my classes with the knowledge that even if I don’t exactly love the subject, I will be challenged and pushed to do my best. I want people to acknowledge that the importance of high school isn’t what comes next, but what is happening right now, and taking risks is what makes high school exciting and engaging. This is the last time in our lives that we will have access to free, public education, and I would like to be able to do what I believe is best for my learning.

Kristen R Westman

May 3, 2025 at 9:09 pm

Sofia, you have a very mature attitude about the ends of education, and I predict you will love the greater freedom of college. Hang in, it’s coming.

You are a wonderful writer, too!

Linnette Wolfberg

Mar 22, 2025 at 9:02 am

Thank you for sharing your perspective. Well done!

Mike Wilson

Mar 21, 2025 at 4:37 pm

Great article!