Picture perfect perception

February 26, 2016

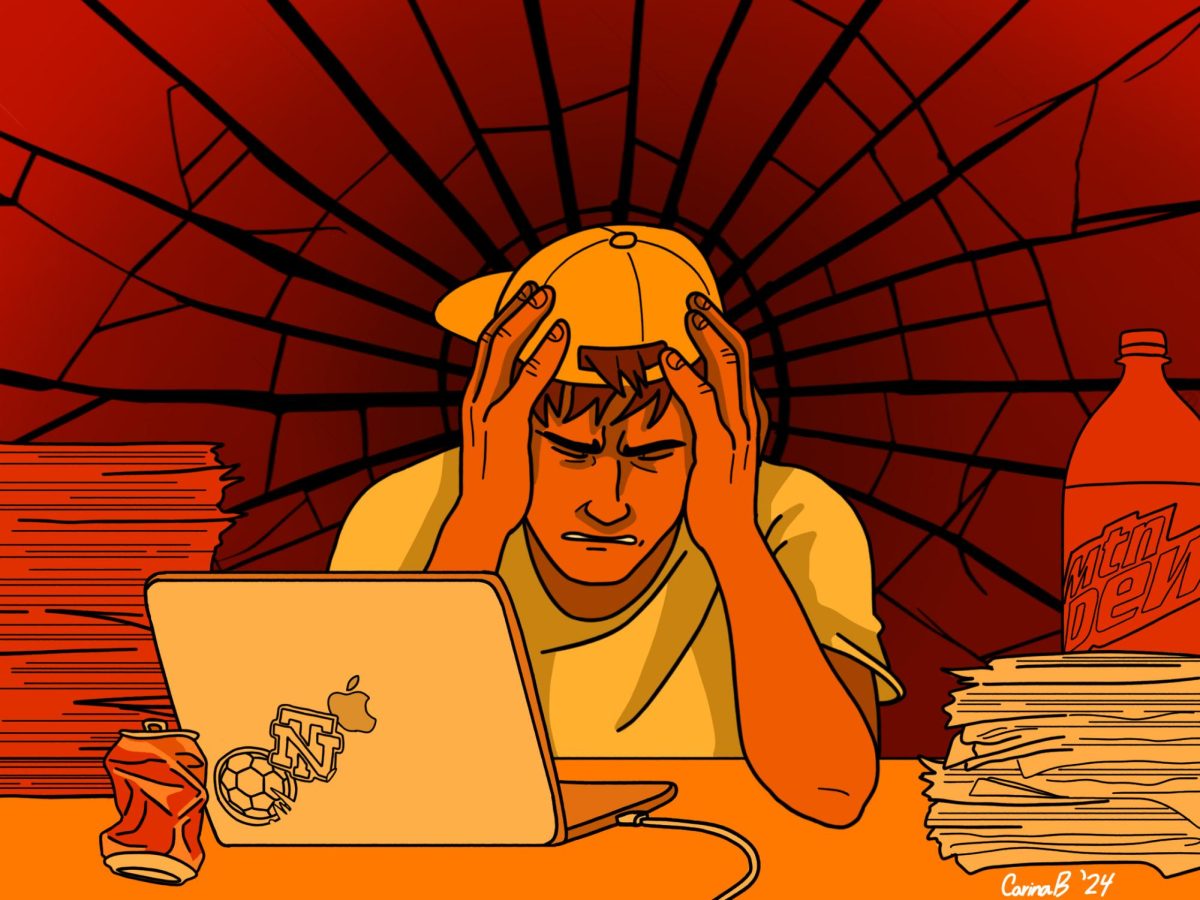

Two weeks ago, I worked press for a big convention of over 2400 teens. All but a few photos I took are of people, and most of those people are standing close together with big smiling faces. I took close to 4,000 pictures which amounts to about 1,300 after editing.

My editing process tends to be pretty standard but also pretty strenuous, and if you’ve been paying attention to this publication for the past few months now, you may have noticed what I do. To keep it short, I generally play around with the exposure and contrast, fiddle with highlights and shadows, and if a picture is out of focus or generally unsalvageable, I delete it. I only delete photos that are of poor technical quality.

I also have a somewhat unorthodox practice of showing people photos right after taking them so they have the option of reshooting or adding more people. The people I take photos of generally praise me for showing them the shots, but typically, I only push for reshoots when my focus is off or I expose the picture incorrectly.

One of my biggest frustrations I run into as a photographer is when people ask me to retake a perfectly good picture. “Oh, I look terrible in that picture! Can you take it again?” is something I hear all the time. I usually try to convince those people that they look great and it was a good picture (the vast majority of the time, it is). But sometimes they won’t have it and just push harder for a reshoot, to which I reluctantly oblige.

At first, I got frustrated about this because I thought they felt I wasn’t properly doing my job as their photographer. I took it personally because I thought they were mad about over exposure or saturated colors. Maybe it was because there was another guy in frame that they didn’t want to be.

The real and sad truth is that they were self-conscious. They simply didn’t like the way they looked and they thought that by asking me for another photo, they would get a chance to make a better smile or have their eyes opened more or look skinnier. The unfortunate truth is that the people I’m taking pictures of just don’t like how they look, and no amount of me reassuring that they look great will let them believe me.

This mentality is understandable. Nearly every published photo of a model is retouched or altered in some way, whether it be a simple contrast boost or a complicated alteration of the model’s overall body shape. This can cause people, especially girls, to remain dissatisfied with their self-image, especially if they aren’t aware of the level of retouching that models undergo before publishing.

According to The Council on Size and Weight Discrimination, young girls are more afraid of becoming fat than they are of nuclear war, cancer or losing their parents. Nearly a quarter of girls 15-17 would consider plastic surgery (PR Newswire) and about 30 million people in the US will undergo a “clinically significant” eating disorder in their life (NEDA).

These statistics are caused by media, and therefore we have a responsibility to stop it. If photographers and fashion publishers keep perpetuating the idea that people can only look good after Photoshop, then self-image will only worsen.

France has already started this push to raise self-image with a Photoshop regulation law and a law to promote healthy models. The country has created these laws to combat its anorexia problem and requires all models to present a doctor’s note with a clean bill of health on it. These laws are a start to a future of better body image.

The first step to creating a better environment for impressionable teenagers is to reassure them that they are healthy, and the best way to do that is to showcase models in magazines that look healthy and strong. The media has to make the goal for health and wellness accessible, not a figment of our imagination as exhibited by the impossible images we see today.

I love seeing beautiful people smiling at me through my viewfinder, and there’s a level of satisfaction that comes from accurately capturing the moment. That satisfaction on both the photographer’s and subject’s side is ruined by this dissolution of positive body image, and it’s really unfortunate that we, as a society, are chasing unicorns to love ourselves.