Think before bragging about spring break adventures

“Staycationers” may feel left out during spring break chats

April 15, 2016

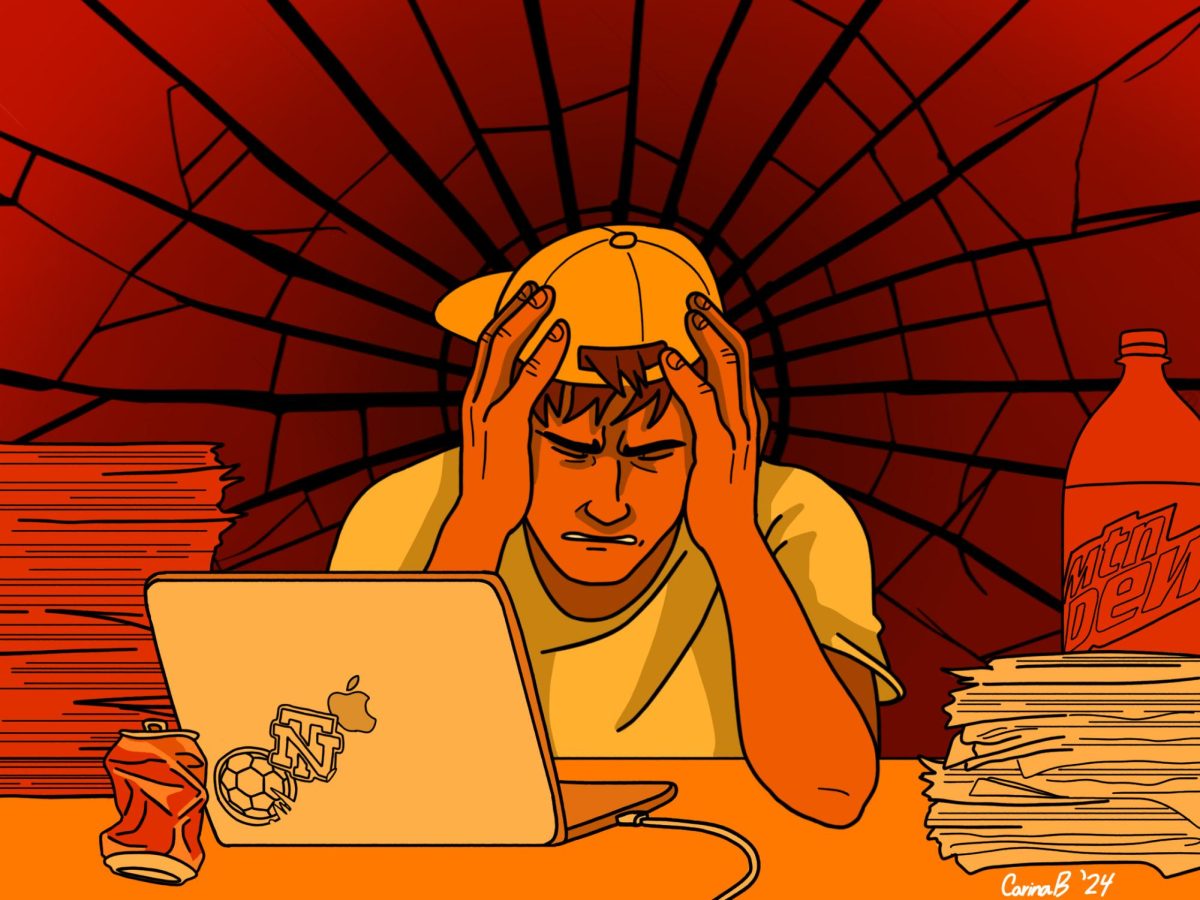

While there seems to be a universal perception that most students travel to expensive places over spring break, discussing vacation plans in advisery and class remains controversial among students and teachers.

“If you didn’t do anything as exciting as other people, you can feel kind of left out or bad,” senior Michelle Cheng said about discussing spring break plans. She explained that this can be particularly bothersome in advisery, a place where break plans are often shared.

Cheng thought there’s a perception that many students at the school travel to expensive locations over break, even if that might not be the case.

This perception forms when your entire friend group is traveling somewhere and you’re the only one staying behind, she explained.

Senior Amrita Krishnan agreed with Cheng, adding that social media serves to amplify this mindset. “Everyone posts pictures of their destination on Facebook and Instagram, so becoming a staycationer almost has a stigma attached to it.”

Because of this issue, art teacher and adviser Gardiner Funo O’Kain is careful not to turn spring break conversations into a compare/contrast situation where everyone is forced to talk.

Funo said that for other adviseries with different dynamics this may be different, but feels that her advisery requires more of a supportive environment “where people can appreciate whatever anybody’s doing and see that whatever you’re doing has its merits.”

Junior Connor Warshauer, on the other hand, thought that talking about spring break is not that big of a deal. He understood why staycations might make some kids feel excluded, but explained that because you can still have a lot of fun at home, talking about it is fine.

Junior Griffin Dunne agreed, explaining that students can enjoy themselves and do interesting things even if they stay home. Dunne himself stayed home for spring break for the last three years without feeling left out, because he always had a great time.

Spanish teacher Tonya Piscitello agreed with Dunne and Warshauer that contrary to popular belief, staying home does not mean being bored.

“You could have done really exciting things, like what if you stayed here and went to a Blackhawks game?” Piscitello said. She added that some kids will answer that way, but most don’t.

Piscitello said about talking to students who stayed home, “It’s consistent, it doesn’t matter what break it is, immediately they say, ‘Well, I just stayed here.’ And immediately the tone and everything about it tells you that there’s this air of ‘I didn’t do something as exciting.’”

Funo agreed with Piscitello that students who stay home over break usually throw in the word “just” or say that they did “nothing.” “It does seem like maybe they have an internal expectation that they’re supposed to live up to some kind of fantastic spring break,” she said.

Piscitello thought that a possible reason for this phenomenon is our drive to always do something.

“I try to help students see the value and worth of sometimes doing nothing. The problem is, we aren’t programmed to do nothing,” she said.

Junior boy’s adviser chair, Gregory Sego, disagreed. “As educators, as people who care about young people, we want to see kids engaged in something,” he said, referring to spring break.

Sego added that this does not necessarily mean academics. Especially nowadays, kids can use the Internet to explore their interests and expand their horizons, he said.

Sego explained that teachers often ask students about spring break plans out of genuine interest. On top of that, they ask in an earnest attempt to get to know their students better.

“As a math teacher for 20 years, I wanted to get to know my students beyond their math abilities. I feel like those appropriate and respectful connections help to build and support a mutual, respectful and professional working environment,” Sego said.