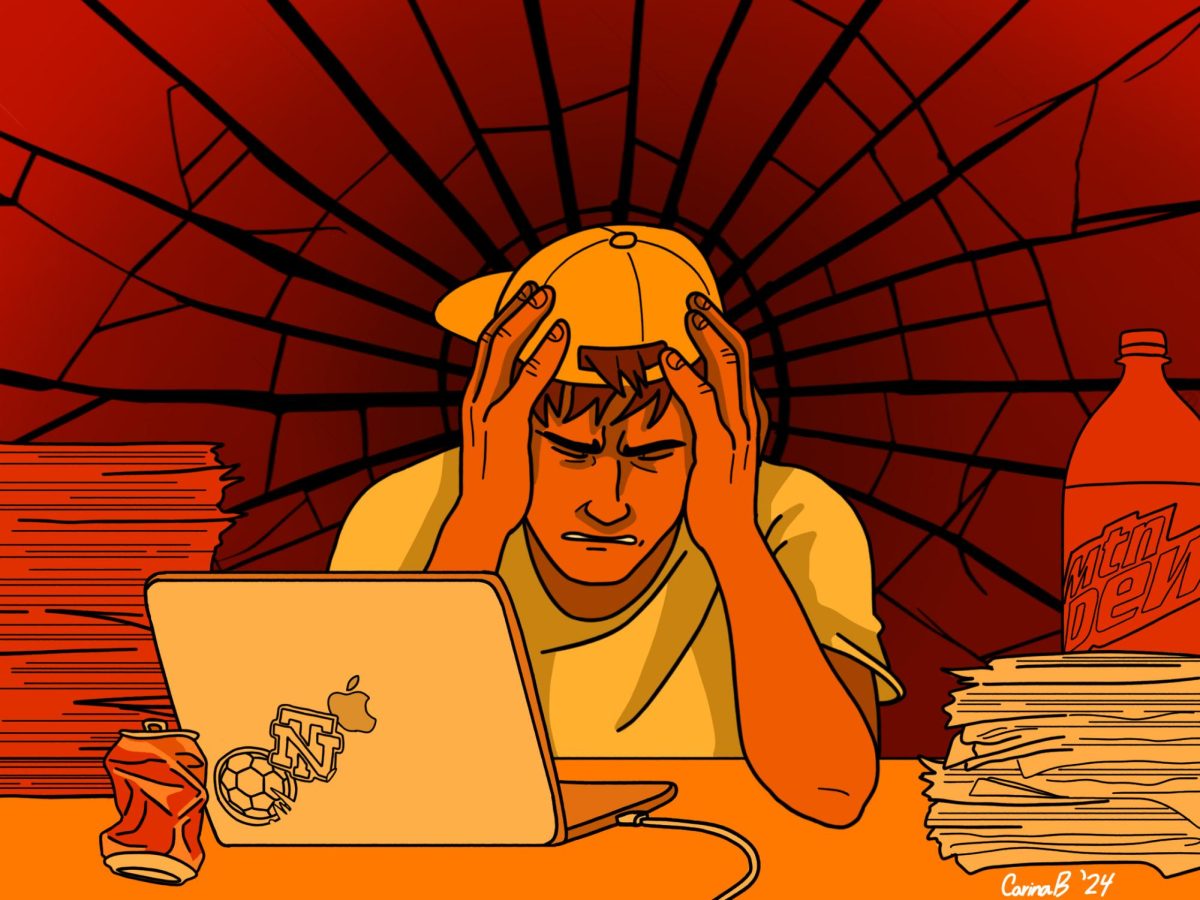

Do finals really matter?

Department Chairs say students’ grades don’t change much with exams

While students often spend their January freaking out over finals, department chairs from Mathematics, Science, and English all say that most don’t really affect grades, and that the role of the final exam is ambiguous.

Math Department Chair Mary Lappan says that the majority of students will perform similarly on final exams as they have throughout the semester. She said there are always a few students whose grades are more volatile, but it’s a significant minority.

“A few kids that have borderline grades will either go up or down if their grades are right on the line and the final exam cements it one way or the other. For the past few years in my classes, one or two kids get a slightly higher grade and one or two get a slightly lower grade, but it’s pretty rare.”

Science Department Chair Jason English estimates that roughly half of students are in a position where their grade could change up or down due to a final.

“A number of students walk into final exams with their grades locked. It doesn’t matter how you do– your grade can’t move very much. There are some students whose grades can move up or down, and those students certainly put in more time and energy into getting ready for the test, and usually for those students their grade goes up.”

English Department Chair Edward Zwirner says that for his classes, he didn’t really treat the final like a traditional cumulative exam.

“To me, a final exam was no different than other assessments I gave throughout the year in English. It was just a longer period than we used to have when we had forty minute classes. You give students a little more time to write, and you could assess their reading at the same time. My final exams were often on the last unit of study. It was never a cumulative exam– they were just taking what we had done recently and ending that unit.”

For Lappan, the final exam process isn’t about the score students receive.

“Final exams aren’t really about grades. I know kids think about it that way. It’s more about the review and the reflection and looking back at the things you thought were hard back in September and it all comes together.”

Math teacher Keely Burns, who teaches Algebra 2 and calculus, says that she takes more than the final into consideration when calculating students’ semester grades.

“I don’t want one test to make or break anything, so I put that grade in but I also look at the overall semester. But to me, [the final is] not as much of a huge piece of the grade as I think some students feel like it’s going to be. If you’ve done your work all semester, it rarely does anything dramatic at all.”

Zwirner has a similar policy for students who were negatively affected by his exams.

“If someone had a difficult exam experience I almost never let it pull them down. It was generally a benefit.”

For Zwirner, a cumulative final in English is unnecessary, as is laying out the entire week for exams.

“We don’t need final exams. And now that our periods are eighty-five minutes long, we have longer blocks that we could use for a longer assessment if we wanted to any time we want to do it. I don’t see the need for a final exam week.”

However, there are still problems with having exams in a block schedule format, according to Lappan. Extended time raises issues, as does the ability of teachers to give one universal assessment that they can compare across classes and years.

“[Giving one final] gives us data about the course and the students this year that we wouldn’t get otherwise, and doing that by class period is really hard because students talk and it takes three days to get all the way through the class periods.”

Zwirner also sees the issue of the possibility of cheating, but says that having all students take the exam on the same day will solve that problem while eliminating the need for an exam week.

“If you didn’t want students communicating with each other about what was on a cumulative exam, you have to have two versions of a test. That is solved by having an exam day where everyone takes it at the same time. There could be a reason to have an exam day for a particular discipline, but that would have to be something that was articulated and clear.”

Lappan said that while the exams are helpful for students and teachers in many ways, they aren’t as important as many believe they are.

“I think [the exam] is helpful. Is it a necessary ticket to the next course? No. It’s a nice data point, but there are others.”