Absenteeism emerges as schoolwide issue

As attendance issues grow, school takes action by proposing new policy

AP

Administrators and teachers from all departments are concerned about students consistently missing class and essential learning content

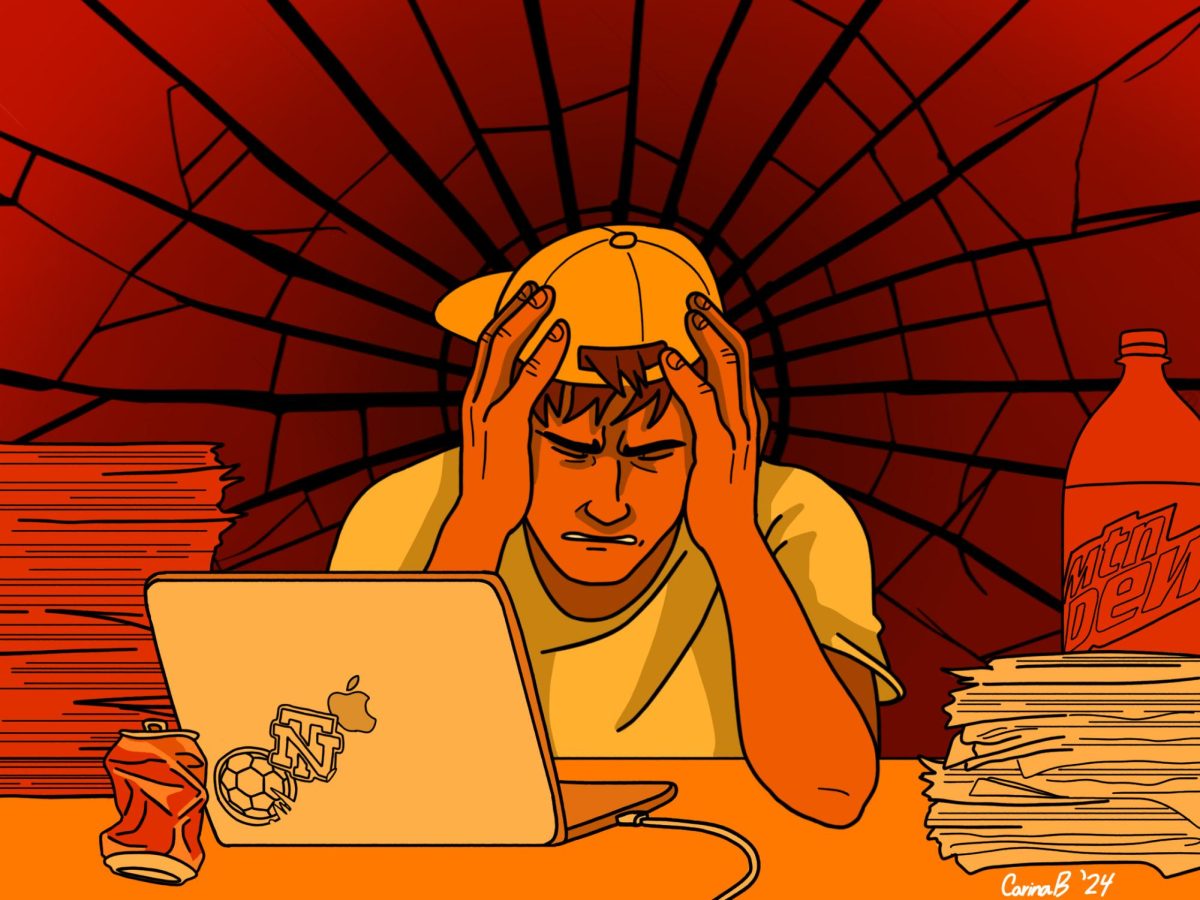

Attendance has become an issue at New Trier, according to its staff, and the effects of absenteeism are much wider than some students might think.

The Assistant Principal for Student Services, Scott Williams, reports that more than a fourth of the student body miss ten percent or more of the school year. This is equal to a month of absences over the year, and some teachers aren’t happy.

Chemistry teacher Laura Hessling is concerned about these statistics.

“It’s not just about what happens to us as teachers, but the impact it has on the students.”

The consequences of absences, according to Hessling, can create a loop of missing school due to the stress caused.

“When you miss multiple classes, the work piles up. Missing work leads to more anxiety, more stress. But not only that, in lab science you’re missing out on the collaboration with lab partners. The time a teacher spends on helping students catch up can take away from students that have been present, which is more of an issue.”

Administrators agree. Gail Gamrath, the assistant principal of the Northfield campus, believes the issue became amplified post-COVID because of a mindset change.

“[Since COVID] adults don’t have to go in person as much anymore in their job, so that’s trickling down [to students]”.

School avoidance, in Gamrath’s eyes, in part could be a symptom of students prioritizing their own mental health, especially since the school implemented the allotted five mental health days. But she believes the impact is quite negligible.

“I don’t know if it made a huge difference. Some of those families would’ve kept their kids home anyways,” Gamrath said.

Williams believes that mental health days help the school check in on students, know where they’re at, and why their attendance may be poor. Overall, the school tries to meet students where they are at and go from there. The first step is parental involvement.

According to the Board Meeting Notes for Feb. 21, “Tier 2 [of absence prevention] is early intervention, where students are missing 10-19% and includes further communication with the family by the adviser to better understand why students may be absent, problem-solve around it, and monitor the situation.”

If that doesn’t work, the school has to do more. Gamrath states the next step is gauging the situation.

“When we’re starting to get into the twenty percent [absent rate], we have a School Avoidance or Refusal Assessment where students fill out reasons they’re not coming to school, the parents fill it out, and we take that as more data and see what is in the student’s control and what’s not,” she said.

To motivate students to attend school when they’re chronically absent, Gamrath describes a three destination program. You’re either at school, at the Health Services, or seeing a doctor.

“You can’t just stay home without seeing a professional,” she said.

And there are consequences for missing school as a chronic absentee under close surveillance.

“[If you miss a day unexcused,] technically there should be a zero for that day’s work, but that gets a little tricky because then kids fall into a hole,” said Gamrath.

Next school year, Williams proposes leveraging privileges to encourage students to attend school consistently considering the severity of this issue.