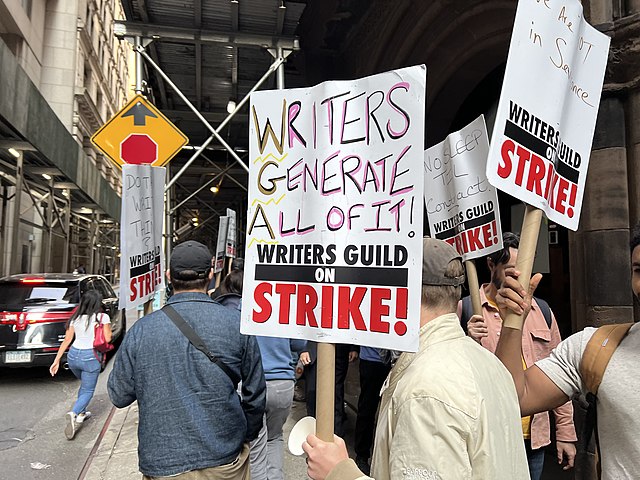

The Writers Guild Association has agreed to a three-year labor contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) after 148 days of striking.

The alliance includes multiple high ranking CEOs of corporations such as Netflix and Disney, who at first refused to make any concessions to WGA, but eventually agreed to a contract featuring streaming compensations, increased minimum pay over the next three years, guaranteed protections from AI, and the removal of inadequate staffing. SAG-AFTRA, Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, also went on strike on July 14, and signed an agreement on Nov. 9th, with a lot of similarity to the WGA’s contract.

The writers started striking on May 2, 2023, halting all productions as WGA members protested outside production sets and media headquarters. In response, AMPTP corporations tried several tactics to disrupt protests, including trimming the trees to erase shade for protestors from the scorching Los Angeles sun, where most writers are based out of.

“Although the writers and studios are mainly based in LA, the thousands of jobs that depend on production across the country, especially in Chicago, like scouting and editing are not working, which hurts the local economy,” Brett Neveu, writer and a strike captain for the Writer’s Guild East, said.

To better understand why writers were willing to go on strike, first one has to understand the demands of the WGA, and more specifically the issues that they are concerned with.

“I heard from people involved in the strike that writers were holding out for a fair deal regarding AI and streaming,” James Syrek, a former TV writer and current film teacher at New Trier, said. “There were new avenues of revenue that needed to be shared between the studios and the writers.”

This issue with developing tech has been a problem that plagued writers all the way back when TV channels began to first stream movies, as the writers then wanted to be paid for their work being streamed. The argument over proper compensation developed further as the work of the writers began to be spread more and more across differing forms of media.

“The issue with compensation is that we didn’t know how many times our works were being streamed because the corporations hid that from us, so we didn’t know how much we were owed,” Neveu said. “In the new contract, now the corporations either have to directly tell us or tell a middleman the entire number of streams.”

Proper pay was also linked to inadequate staffing practices. There had been a practice of hiring one or two TV writers to create the script for a show, assigning a lot of work for not enough pay.

“A lot of time and there are no guaranteed residuals. It was like, here is a little job for four weeks that is supposed to last you for a year? It was not enough money to live upon,” Neveu said.

Another issue discussed was AI, as the writers wanted protection from the threat of AI completely replacing them. While nothing can technically stop the studios from using AI to write scripts for them, the WGA seeks greater action against the more pervasive uses.

“I think that ideas need to be protected,” Syrek said. “Like if I write a draft on a script, bring it to a studio, and they take it to AI [to modify], am I still the writer, or is the AI still the writer?”

Despite the AMPTP agreeing on new contracts that address these concerns with both WGA and Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, this will not be the last strike that most of us will see from either the WGA or SAG-AFTRA.

“With new innovations, there are new forms of revenue, and the writers want those profits to be shared, but sharing the profits isn’t what corporations want to do. Then we have to start fighting about it,” Neveu said.