Tests won’t determine your future

At the beginning of this month, 8th graders flocked to NT for a placement test that will help determine their classes for High school.

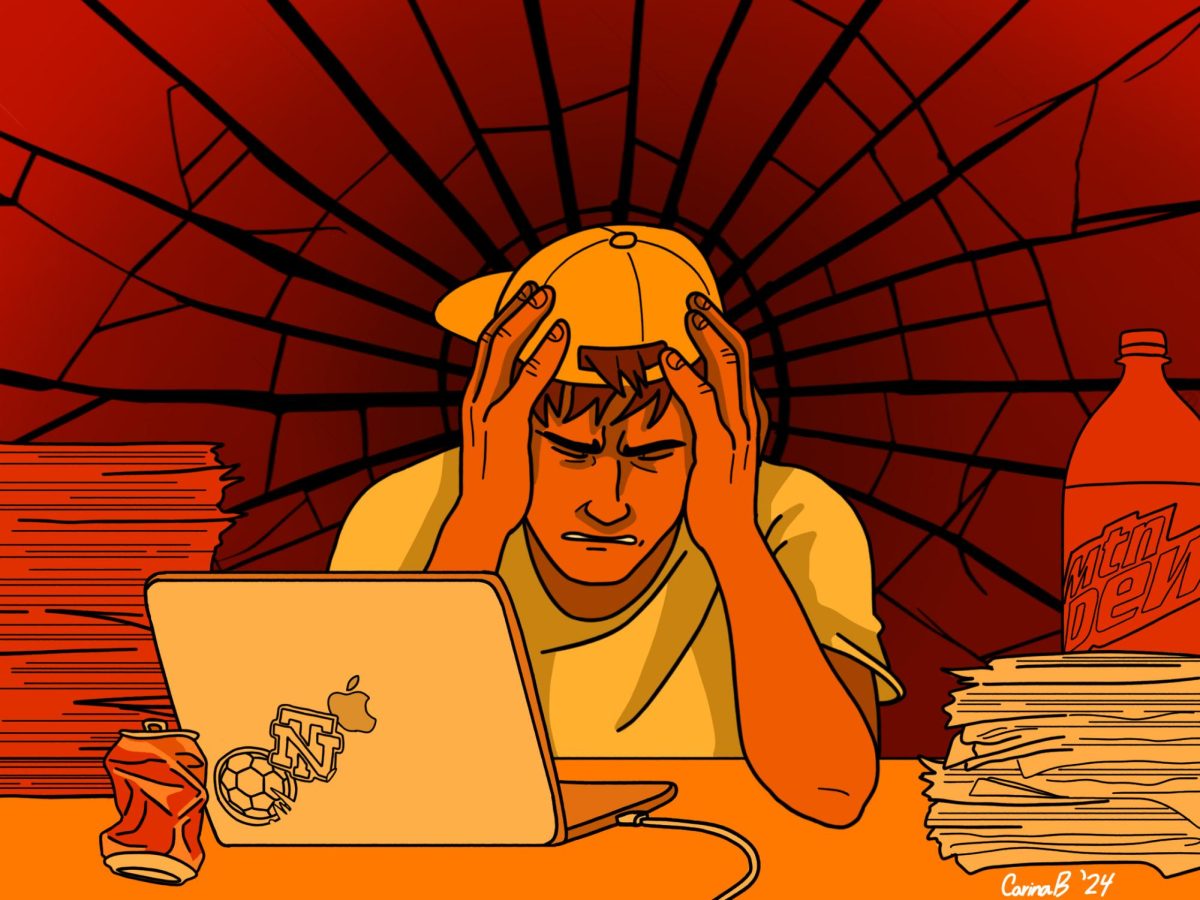

The anticipation and excitement of finally being at high school, however, was outweighed by the stress of a test that seems to dictate the rest of their lives, for some.

Although these tests aren’t the only factor influencing an incoming freshman’s schedule, the four-hour test is the most tangible determinant. The process also includes detailed evaluations from 8th grade teachers who assess each student’s critical thinking skills, class participation, homework completion, interpersonal skills, writing skills, independent learning ability, and analytical skills.

The stress and obsession that 8th graders and their parents can get sucked into with these placement tests definitely doesn’t match the levels reached during the testing and college process, but it does appear reminiscent.

But it’s also a ‘chicken or egg’ dilemma where the stress of the placement test is part of a larger stress about college, since many feel as if high school placement test results could in some way be predictive of a student’s acceptance to Harvard.

And, technically, the classes you place into could have jurisdiction over your course load and your schedule which colleges take into account, but the problem with this mindset is the emphasis placed on fixed determinism.

‘If I don’t get into the right classes, I won’t get into a ‘good’ school. If I don’t get into a ‘good’ school, I will live a miserable life and won’t be able to sustain myself,’ is what it all seems to imply.

This line of thinking demonstrates the vulnerable underbelly of fear of the future dictating all of our decisions. Fear in general, even fear of the future, is not inherently unhealthy in moderate proportions, but when it usurps our ability to be happy and find autonomy in our own lives.

Placement tests and ACT tests and any other events that appear to hold the power to determine our happiness certainly determine some things, but not everything. The emphasis we place on them is a mirage to distract us from the fact that our lives are much more variegated and complex than this perspective allows.

It feels comforting to attribute our future success to something tangible. If you do well on an AP test, you will do well in life. But a good score has little bearing on actual life. Success and happiness and other lofty abstractions are composed of a myriad of things and can’t be simplified to one number.

Tests are scary—no one knows what to expect when sitting in a room for hours on end filling out a never-ending barrage of tiny bubbles.

But past eighth grade and past freshman year, few people even remember the experience—or the results—of their tests.

It’s rare to not know someone who’s switched levels a few times, adjusting to the difficulty of the class and the demands of other parts of their life.

In reality, things change. New opportunities arise. We meet new people. We change our levels if they’re not right for us.