A guide to discussing while uninformed

I sat down to write this article about the Paul Manafort trial and my opinions on how his sentence was only (after being doubled a few days after the initial decision) seven and a half years long. This is obviously something I find frustrating–why should a rich, public figure be given a shorter sentence than someone of lower standing in the same situation?

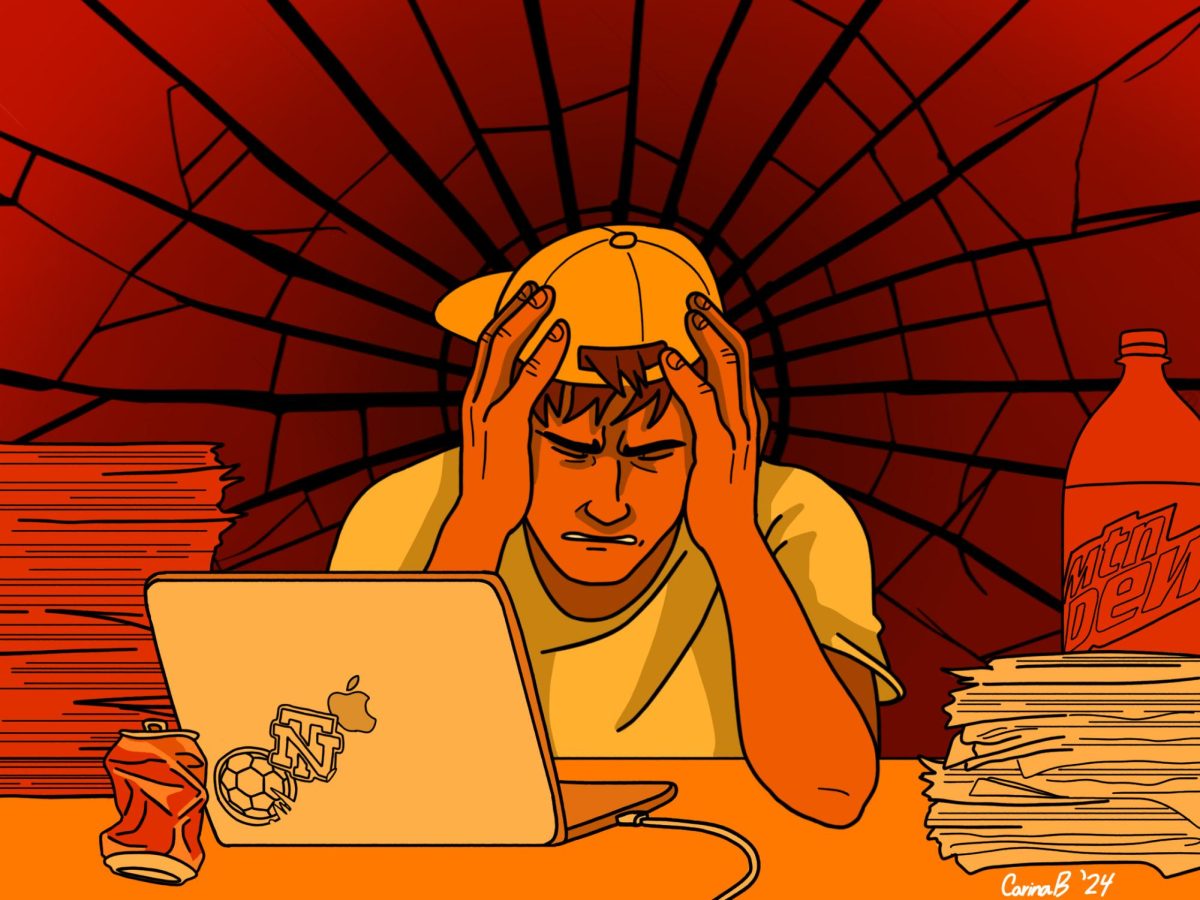

I then realized that I have absolutely no answers to this question. I don’t even know how to approach such a big topic. I’ve read some articles from The New York Times and The Washington Post, but do I actually know enough to write about this?

A similar situation happened in my English class the other day. We were discussing the meaning of morality and I just sat there in the corner wondering if I actually knew enough about this topic to talk about it.

The answer is, well, no. But that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t try.

I then began realizing that I should just write about how to talk about what we don’t know enough to talk about. Then it came to me that I don’t even know enough about how to talk about what I don’t know enough to talk about.

So I reached out to some friends and one gave me the following quote from Socrates: “The only true wisdom is knowing you know nothing.”

That makes for a good starting point. The first step in having these difficult discussions is being aware of your own limitations. No matter how many news clips you see or articles you read, you’ll never know everything.

We’re all experts at some things and novices at others, so don’t make people feel bad about what they don’t know. The same goes for yourself. It can be embarrassing to be thrown into a conversation in which you have no idea what you’re doing. Embrace this. Admitting what you don’t know is better than hiding it.

Step two, ask questions. We’ve all heard teachers say that there are no such thing as a “dumb question.” That can seem wrong, but in this case, what you think to be an overly basic question may be something that everyone is trying to figure out. For example, what did Manafort actually do? (okay I know, but isn’t ‘collusion’ super vague?)

These conversations should be ones in which everyone is learning. This learning, however, doesn’t have to be just understanding a new viewpoint. It could be learning the facts of the situation as well.

We’re often told to not have an opinion until we know all the facts, but conversations are driven by opinions. Of course it’s better to hold off on having a strong opinion until you know the situation from front to back. However, people don’t typically operate this way. We form opinions on first look, which is okay, but it should be acknowledged that this isn’t a totally informed viewpoint.

In addition to asking questions, if someone else asks a question, don’t laugh it off. Let this person learn. And if you don’t know the answer, or don’t feel qualified to answer, seek some outside source. Luckily nowadays it’s easy to consult the internet whenever you’re unsure of a fact, but don’t forget that friends and family can also be resources for understanding.

Step three, know who you’re talking to. Is this a person who sways either right or left politically? What sort of news sources do they use? Are they overly emotional? Do they hold a grudge against a certain type of person? All these characteristics can cause someone to, either intentionally or unintentionally, present the facts in a biased way.

To this point, it’s essential that you don’t take whatever someone says as fact right away. Even if you trust this person, check with other reputable sources.

Lastly and most importantly, when you’re talking about something that you are unqualified to talk about, be open to being wrong. Opinions form quickly, but should be malleable enough that new facts (please check your sources, though) or viewpoints can make you question them. If everyone’s opinions were just set in stone there would be no purpose in having conversations at all.

As is evident by me hiding in the back of my English class because I have no idea how to talk about the meaning of art, conversations in which we don’t feel qualified enough can be intimidating. But by letting go of expectations of always having the right answer and knowing exactly what to say, these discussions can greatly inform our understanding.

The next time you’re thrown into a political discussion about something you barely know about, don’t be afraid to talk and share what you think. Just keep an open mind, do your research, and learn.