Suicide and mental illness are real. Let’s talk about it like it is.

Something needs to be said, but I don’t hear anyone saying it.

It’s no mystery that suicide and mental illness fall into the category of conversations people are uncomfortable having and tend to shelve for “later.”

But it’s important to note that these issues are on the rise worldwide. In 2017, the National Institute of Mental Health reported 47,173 suicides in the United States compared to 19,510 homicides.

With these numbers in mind, it’s absolutely pertinent that we have discussions about mental illness and suicide so we can more thoroughly be educated about it, enabling us to better combat these issues which are hurting those we care about.

Our school isn’t the only party guilty of avoiding the issue; the larger culture has also been neglecting it. The statistics clearly show that suicide is an ever growing issue, yet suicide coverage, whether in schools or the media at large, is almost nonexistent.

But just because we have become accustomed to the silence doesn’t mean it’s okay.

After a student passed away last school year, I was hoping some conversation – any conversation – regarding suicide and mental illness would happen. But we never got one except four articles our newspaper published on the subject.

While I’m all for making efforts to initiate these conversations by writing for the school paper, I don’t think students should hold the responsibility of leading the charge on topics such as this.

Ideally our school would take on the job of facilitating these discussions, but after the silence that followed last school year’s death, and now the student death from November, I’m not confident it’s ever going to happen.

I don’t think it’s the school’s intent to cause distress or harm to their students, but it doesn’t change the fact that their avoidance of these increasingly important issues is doing just that to some of us.

The fact of the matter is the silence is deafening and has been for a while now. Though it’s uncomfortable to talk about, the more we ignore this issue the more it will persist and worsen as the stigma remains unchallenged

I completely understand families may request and fully deserve privacy, but that doesn’t mean we can’t talk about mental illness and suicide. Nor should we wait for tragedy to befall our community to initiate these discussions.

There is no simple way to address these topics – striking the balance between glorifying suicide and completely disregarding it is difficult. But staying silent isn’t the right answer.

In order to avoid glorification of suicide, these conversations should focus on the varying causes of self- harm, not on the specific manner and reasons for how and why someone took their life.

Yet I hesitate when I suggest that the school start these discussions because I’m not confident their efforts would foster an open and honest conversation. And I mean conversation, not a lecture or presentation. There’s a difference.

What I’ve often been troubled by when schools deliver presentations or lessons on mental illness is how they make it seem as though depression or anxiety is something easy to spot.

While I myself don’t struggle with a mental illness, I do know what it’s like to support – to the best of my ability – a friend who struggles from depression.

Let me first say, the classroom presentations I’ve been force fed in my years of school didn’t help me

– I had no idea my friend was going through such a challenging illness as depression. They were sociable and upbeat at school so there didn’t seem to be anything to worry about.

People, especially students, are good at hiding their emotions, and it’s misguided to suggest that a friend, classmate, or teacher will simply know if someone is struggling.

It’s possible that signs may be visible in someone, but this is no one size fits all matter. There isn’t, and never will be, a clear-cut answer when it comes to suicide and mental illness.

I’m sorry, but I can’t accept the Trevian Tip Line as the solution to every problem, especially this one.

And while we are fortunate to have great social work support, we can’t expect 13 social workers to adequately support New Trier’s four thousand students.

While social work is certainly a good resource, I think the more support someone has the better. And although students aren’t licensed social workers, I believe they can do a lot of good in supporting their friends as long as they have the tools to do so.

Students need to know how to support their friends if they’re struggling and even how to cope with suicide if it comes to affect their life in some way.

Suicide has already indirectly affected me on three separate occasions, which I feel is indicative of the realities we’re being presented with right now.

So in order for students to be properly equipped to support their friends and peers, they need to be educated on these topics. The question is how that’s going to happen.

I understand that it’s easier to have a clear set of instructions or signs to consult if you’re concerned about someone, but this method doesn’t account for the extremely diverse experiences of those who struggle with a mental illness. It does a disservice to them because all of their struggles are then presumed to be the same, which is not true.

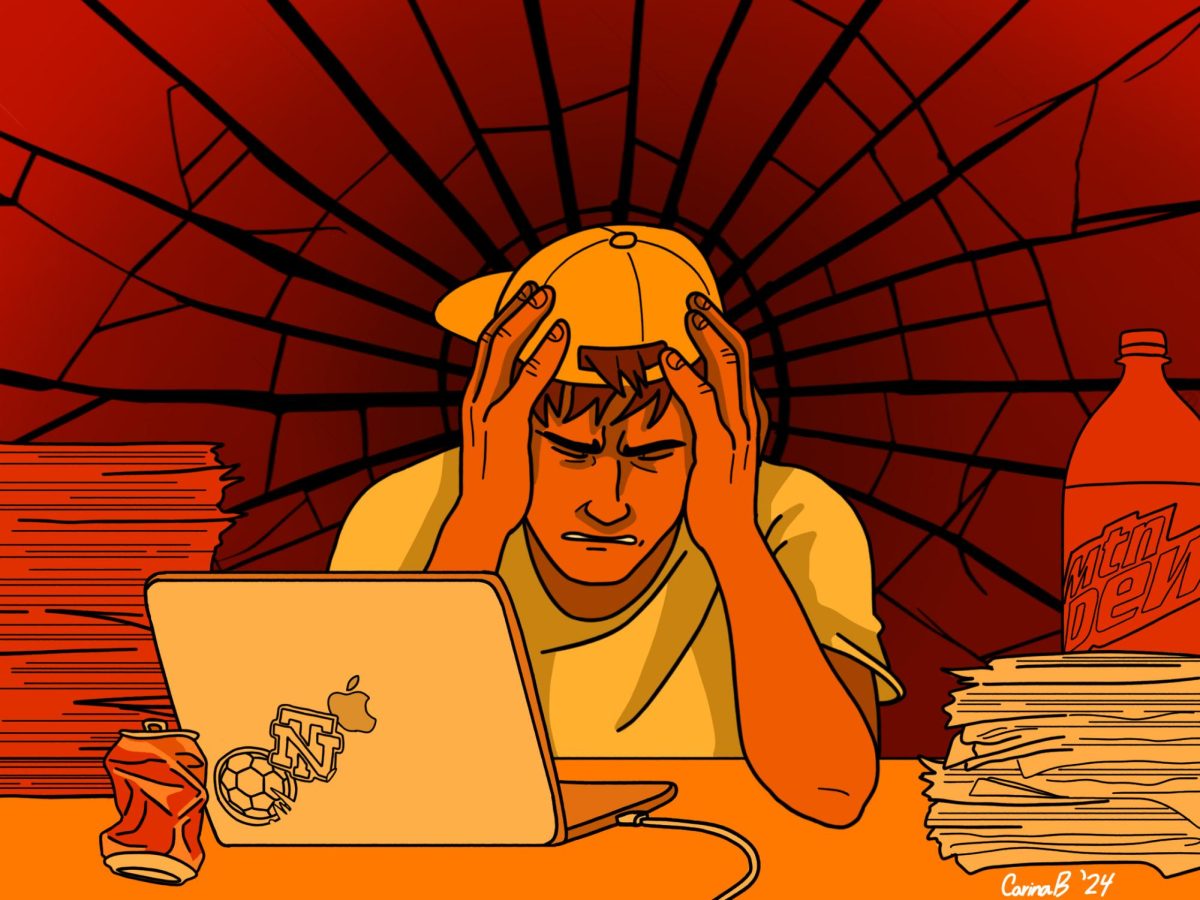

Currently, health classes don’t appropriately account for these vast experiences. While it’s impossible to touch on every single aspect, I think it would be good for the class to address other types of mental illnesses in their curriculum as well as foster deeper conversations which go beyond simple stress management strategies, like taking a bath.

Health class conversations need to be opened up in a way so that those who struggle with mental illnesses are more accurately represented and should also be a way for peers to become educated on how to realistically support their friends.

While I know the school likes to rely on advisers to facilitate difficult discussions, the reality is a number of them aren’t educated on or comfortable with engaging in conversations about suicide and mental illness. Thus, I don’t think this is the avenue to take in addressing this issue.

Instead, I think it would be good to invite professionals to speak about these complicated issues in a seminar day-esque setting. But one day is not sufficient for this topic or any complex topic.

In conjunction with a possible seminar day, I also see value in students hearing from other students who are educated about these issues and/or have personal experiences to speak from. I think it could be beneficial for students who are comfortable having these discussions to lead adviseries in them. This way, the people they’re learning from are their equal, creating what could be a more open conversation since there wouldn’t be as much fear of judgement as there might be when an adult talks about these things.

Whenever I’m listening to someone who has been personally affected by the issue which they

are addressing, I remember what they say and am likely to be more mindful when navigating the subject in the future.

There are many ways to address mental illness and suicide beyond what I set forth, but maybe they can point us in the right direction.

Being friends with the student who passed away last year, the silence was sickening and I remained frustrated for the rest of the year. Now we’ve lost another student and the silence is more deafening, further emphasizing how afraid we are to talk about it.

We shouldn’t dissect the lives of those we’ve lost because we will never find what we’re looking for. But we do need to address this issue which is taking more and more lives.

The lunch mental health information sessions that have begun are a good start and I appreciate the effort, but I think making it an optional activity downplays its importance.

Considering the growing prevalence of mental illness, it’s important everyone is educated about it since they’re likely to encounter it in some capacity in their lifetime.

More people nationwide and in our community are dying from mental illnesses, which as far as I’m concerned, should make the subject the utmost priority to address. Not doing so gives the impression the school doesn’t believe it’s important.

While I don’t think that’s true, their actions indicate otherwise. And actions speak louder than words.