How genocide transformed into turkey, mashed potatoes, and giving thanks

With the 400th anniversary of Thanksgiving this year, White America’s fantasy tale of a commemorative autumn feast furthers the subjugation of Native Americans

For the average American family, Thanksgiving is a time of reflection, where we can take a step back from the stressors of daily life and consider what we are grateful for. We get together with family and friends, enjoying turkey and mashed potatoes, celebrating the loving relationships we have built for ourselves.

However the kinship and community that have largely been attributed to Thanksgiving were not present at the original event four centuries ago. The real story of Thanksgiving, one filled with countless deaths, broken treaties, and stolen land, should push us to critically think about whether or not we choose to participate in the holiday.

My elementary school education taught me about Thanksgiving through a celebratory reenactment. Children would mingle and party while wearing pilgrim-style outfits and munching on tasty snacks—that is until one kid in the first grade had an allergic reaction.

Thanksgiving was portrayed as a 3-day festival to celebrate the union of the Native Americans and the European settlers. Native Americans graciously shared their cultivation methods with the newly arrived settlers, teaching them how to grow corn. After enduring their first winter, the tight-knit Plymouth colony invited their Native neighbors to a festival that honored their partnership.

From a peaceful dinner, history reveals that the European colonizers went on to break the shared peace treaty after treaty, conquering Native lands and causing the death of millions of Indigenous people—a chain of events that make little sense. The pleasant myth of Thanksgiving has created a disconnect in our country’s history, effectively allowing colonial takeover to appear bloodless, as the Native Americans seemingly faded away.

The truth is, the demise of the Native population occurred much earlier than the first Thanksgiving of 1621. Research from the Quaternary Science Reviews shows that by 1620, the Indigenous population of New England had already decreased by 90% because of “Indian Fever,” disease brought by the settlers. Our historic November day of grace aids in concealing this dark history.

So what really happened on Turkey day?

Pilgrims were celebrating their harvest, not through a traditional “thanksgiving,” which entailed fasting and prayer, but more properly a “rejoicing.”

The traditional foods of Thanksgiving, such as mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce, and pumpkin pie, were not present at the pilgrim’s party. The Smithsonian magazine suggests that rather, they most likely enjoyed goose or duck, corn cooked as porridge or cornbread, and various legumes.

The exciting spirit got the best of the settlers, and some of the men began shooting off their guns. Fearing people were injured, the Wampanoag tribe, led by Ousamequin, sent in what was believed to be an army of almost 90 men to check out the scene.

The Wampanoags and settlers had a previously established alliance, which was created because a significant portion of the tribe had been wiped out by disease, according to David Silverman’s book “This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving.” The group of Native men that arrived at the colonial settlement were said to be honoring the aforementioned mutual-defense pact that was instituted the past spring.

Once the celebration calmed down and the Wampanoags assessed the situation, the two begrudgingly spent the next three days together. There was no intercultural fellowship or shared exchange. In fact, during that three day period, pilgrims were exceedingly hostile towards the Wampanoags, perceiving a majority of their actions as threats.

The Natives and pilgrims were united only in their struggle for survival. When the pilgrims built up their numbers and laid a sturdy foundation for white evangelical society, America’s indigenous people were no longer needed.

An American Thanksgiving often emphasizes the “togetherness” that was absent for the original feast. The fallacious fable we toast to every November works to conceal the tortured history of Native Americans.

Rather than quietly disappearing, tribes were forcibly pushed out of their lands, enslaved, and killed. Ironically enough, a holiday centered on gratitude potentially arose from this violence, specifically from the colonizers’ gruesome victories over the Natives.

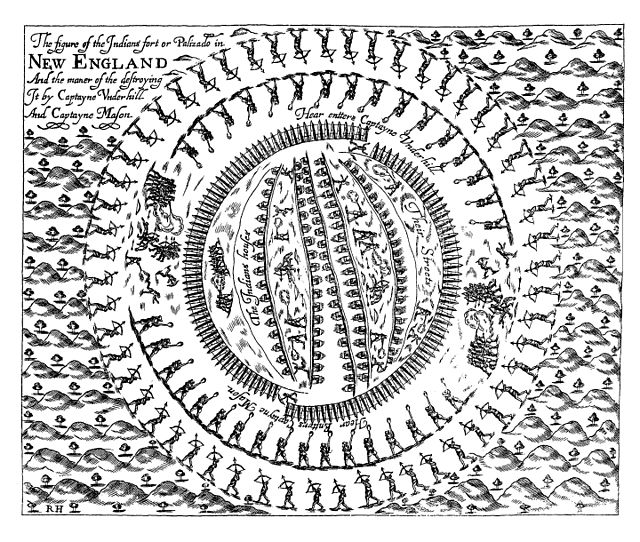

The Pequot War, a three year war initiated by settlers who attempted to steal Pequot land, faced a turning point with the Pequot Massacre of 1637. According to the Zinn Education Project, Settlers killed nearly 500 children and adults of the Pequot tribe by burning their forts. The destruction of the Pequot tribe was honored with a “thanksgiving” of religious reflection and fasting. This day was later deemed a day of celebration by Massachusetts Bay’s Governor John Winthrop.

According to historian Robert E. Cray, Jr., King Philip’s War with the Wampanoag tribe also featured a “thanksgiving.” With a colonial victory, Ousamequin’s son, Metacomet, who had inherited tribal leadership, was beheaded and his head placed on a spike to be displayed for the following 25 years. Remaining peoples of the Wampanoag tribe were sold off into slavery or executed, and of course, the colonizers made sure to give their thanks.

Thanksgiving was finally titled a national holiday by President Abraham Lincoln on Oct. 3, 1863, as a day to thank God for the prosperity of America.

Given its brutal history, should Thanksgiving still be celebrated?

It’s certainly understandable to want to take a day to appreciate everything you’re grateful for. I would be lost without the support of my friends and family. So long as Thanksgiving continues its false narrative of unity, however, we should also take time to acknowledge history.

A main priority of our day of thanks should be recognizing the strength and legacy of Indigenous communities.

Thanksgiving has led to the erasure of the violent oppression of Native Americans, so for non-indigenous people like myself, we should be working towards honoring Native culture, educating others about the true history of America, and continuing our learning of American colonialism and its long-standing impact towards Black and Brown bodies.