Indigenous lands and the myth of New Trier’s founding

Research reveals local Native American land history is a more complicated story

Yoon

The Treaty of Chicago in 1833 gave settlers the right to Winnetka soil, and was signed through threats and intimidation

New Trier High School has been an important feature of the North Shore community since its founding in 1901. Though the land on which the school resides was owned by Native American tribes when it first opened, only 11 of about 4,000 students this year identify as Native American.

The school itself sits on lands previously occupied by Peoria, Potawatomi, Chippewa and Miami tribes. However, the school has never publicly acknowledged this.

In “New Trier: Portrait of an American High School,” the occupation of indigenous lands is only mentioned once: “Significant settlement of what is now called New Trier Township began after 1829, when congress signed the Treaty of Prairie du Chien with the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi tribes.”

What the book fails to mention is that this treaty had nothing to do with white settlers obtaining any land.

Instead, it was the Treaty of Chicago– a treaty that was never mentioned by the school in or out of the book–that gave settlers the right to Winnetka soil, and even then was signed through threats and intimidation, according to Dr. David Edmunds, a professor of American History at the University of Texas.

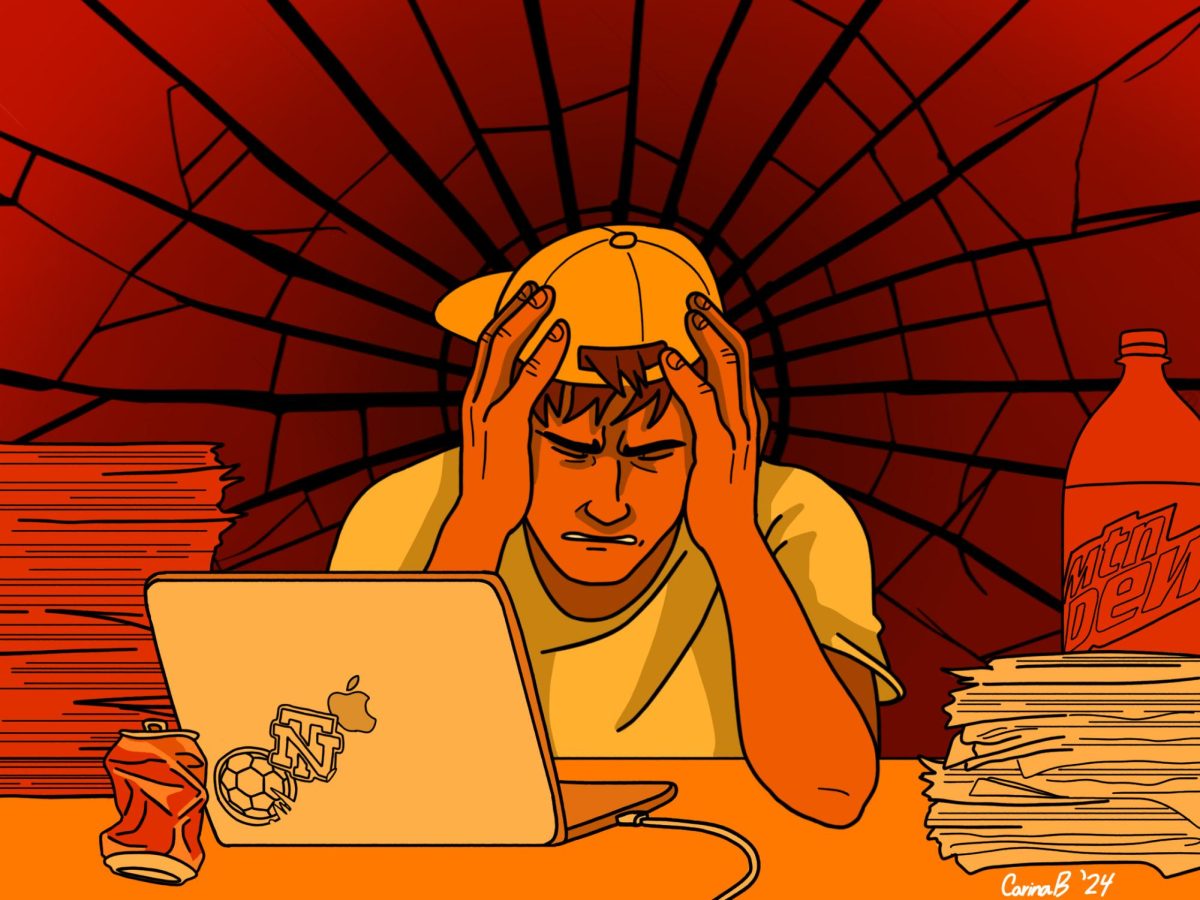

English teacher John O’Connor has led his American Studies classes in extensive research of local Native American communities and their history. This research led the class to wonder why the school has not acknowledged its land’s native origins.

“Nearby institutions like Loyola University and Northwestern prominently feature what’s known as indigenous land acknowledgement; just a statement that helps people understand the origins of the institution,” says O’Connor.

A number of students have brought this up before, citing that because of the size and importance of the school in the area, it should have a proper land acknowledgment on its website. And though the history of the Native American peoples is covered in select English and history classes, it is often only covered in relation to the history of European settlers.

With the cultural awareness arising from the murder of George Floyd last year, some students again saw a need for a statement about land acknowledement.

“I think myself and some other students recognize that our education was failing its students and we wanted to address some of the gaps in that education,” said Erik Liederbach, a 2015 alum who recently sent a letter to the administration to voice his dissatisfaction with the school’s approach to addressing marginalized communities.

Recently New Trier has voiced a desire to change the legacy of Native representation on the North Shore.

“New Trier believes we need to make the identity, history, and concerns of Native American and indigenous people visible in our school community,” said Principal Denise Dubravec.

Dubravec also stressed the implications of a land acknowledgement at New Trier.

“While such a statement could be a part of our overall efforts at raising awareness, land acknowledgements in and of themselves can also be seen as an attempt for institutions to check a box as opposed to taking action to support Native American communities. We want to make sure that whatever we do is part of a larger, ongoing effort to bring recognition to Native American and indigenous people and communities.”

When German settlers found themselves in the land of Winnetka, the lands were not barren. Many tribes were living and had lived in the areas for hundreds of years, and planned on staying. Soon enough, many of these peoples were robbed of their lands. All at the hands of these very settlers, who barely a generation later would found New Trier.

“Indigenous peoples were murdered or forcibly removed from these lands.” says education professor, William Ayers in a blog post, “Over a century later, under a different set of oppressive policies, many were once again coerced to migrate, this time back to the urban centers where their ancestors had earlier been robbed and forcibly removed,”

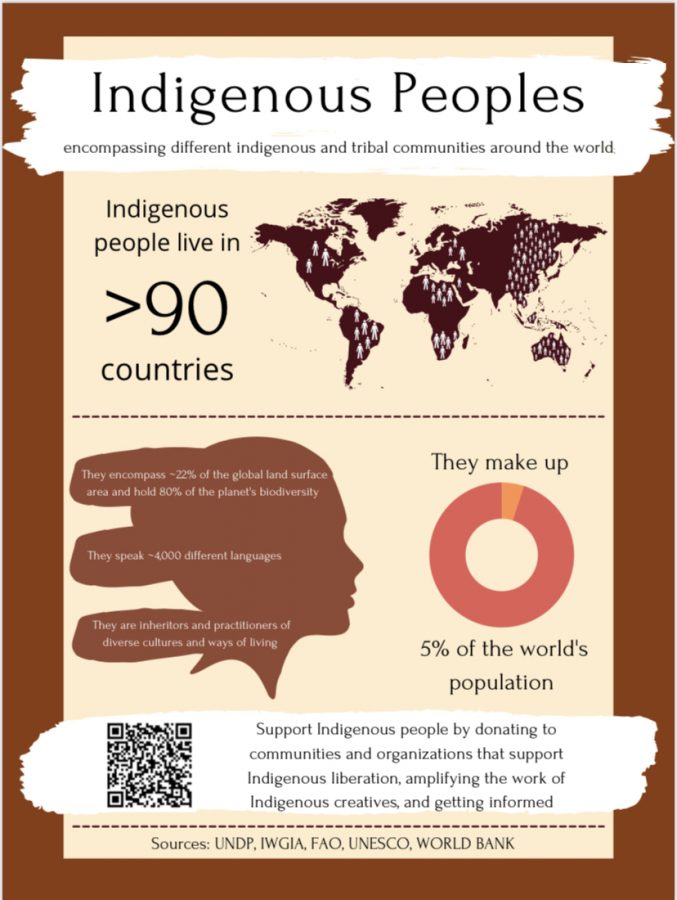

The Indigenous population has been dwindling since their first encounter with colonists, and yet Native American communities are still alive and thriving in communities all over the state and in the Chicagoland area.

“Among the biggest things that I think we learned were the size of the huge number of citizens in the Chicago area who self-identify as Native Americans. I think the population is much bigger than probably a lot of people acknowledge. And I certainly think that it was eye opening,” says O’Connor.

The Chicago area is home to a large and proud Native American community. Among them are vocal activists and skilled artists who have been raising awareness for Native causes including the long struggle over Native land rights.

According to an article from WTTW, “Tribes from across the country congregated here in the Chicago area; it was a central trade hub,” says Heather Miller, the executive director of the American Indian Center in Chicago and a member of the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma. “Oftentimes we forget about that important history, and it’s so often overlooked from the history of Chicago.”

A lack of land acknowledgment is not the first time nearby institutions have misrepresented indigenous peoples, however.

“It wasn’t very long ago that Niles West used to be called the Indians, and they changed their name. New Trier West, of course, used to be called the Indians,” O’Connor said.

New Trier including an official land acknowledgement in its website will not erase hundreds of years of oppression. But creating a space where Indigenous people feel listened to could lead to a more positive future for not only our general community, but the native communities in the Chicago Area.

Professor Ayers, in the same blog post writes, “They raised their children here, created their communities, made sense and meaning for one another, experienced the flowing and the passing of their time together, planned for the future, and buried their dead here.”