Real or fake? New AI tech may be dicey

Deepfakes create challenges in digital world, making new tech unreliable

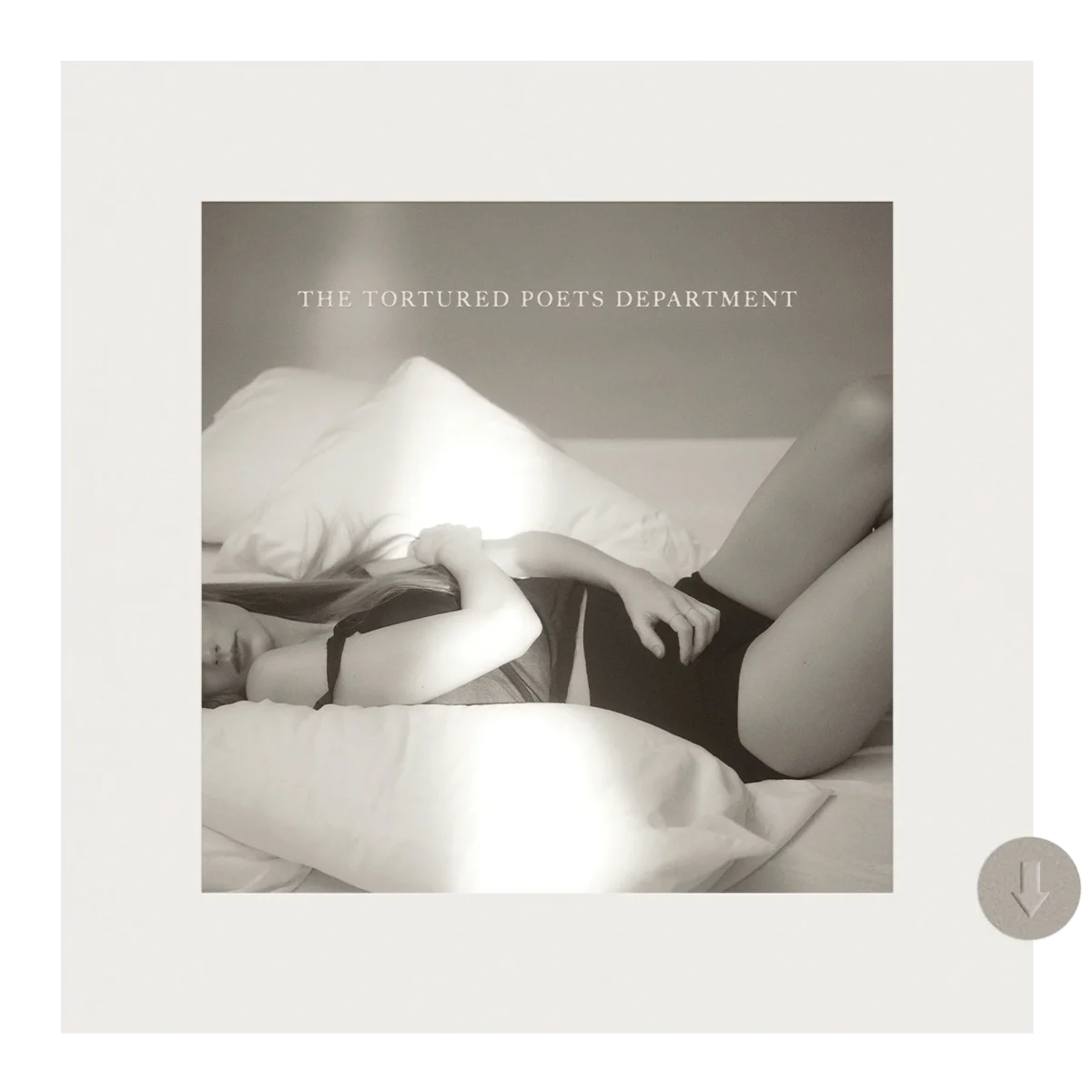

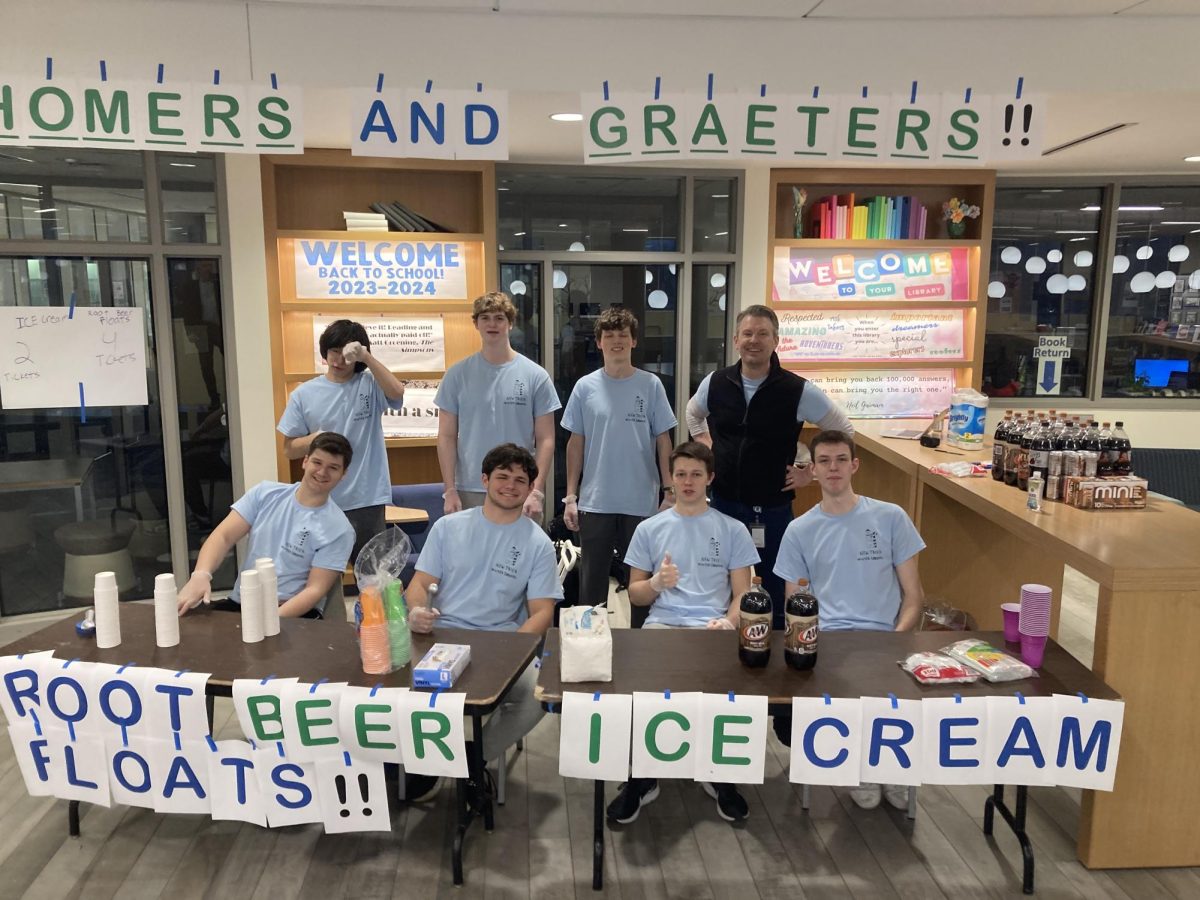

This image made from video of a fake video featuring former President Barack Obama shows elements of facial mapping used in new technology

Earlier this week, a deepfake video of Chicago mayoral candidate Paul Vallas circulated in the leadup to the city’s first round of voting.

The video, which falsely depicted Vallas saying that back in his day “cops would kill 17 or 18 people” and “nobody would bat an eye,” is raising questions about the risks posed by this emerging technology, according to CBS News Chicago.

Although the video was eventually taken down, this came after it had been viewed thousands of times, meaning any misinformation due to the video may have already occurred. The problem, however, is far bigger than Chicago.

Deepfakes are created using artificial intelligence to swap one person’s likeness with another; the process typically involving two AI algorithms that swap the faces or combine voices, creating a more realistic version through cycles of feedback. As the technology behind these videos improves, deepfakes are becoming easier to make—and more convincing.

The technology behind deepfakes have advanced dramatically in recent years, and artificial intelligence software is becoming relatively accessible. Through these advancements, it is also becoming harder to distinguish between fakes and real videos. In a study from 2021, it has been found that every time a deepfake detector is used, its effectiveness is lowered, because the people who produce these deepfakes are able to reverse engineer and counter the new developments.

However, countermeasures to deepfakes have also dramatically improved as well. In 2018, a study done by Cornell scholars, Korshunov and Marcel, found that AI tech produced a false result 95% of the time when identifying whether a video was deep fake or not.

In 2023, a researcher from Northwestern University found that AI tech could detect deepfakes with a 90% accuracy rate.

In 2018, a group of U.S. researchers at the University of Albany found that the people depicted in deepfakes don’t always blink normally, which is one way

to spot a fake. Other ways include bad lip synching, lighting issues, and problems with more fine details of the person such as skin and hair.

In other words, the human eye is largely able to distinguish between reals and fakes—for now. Additionally, the number of deepfakes online has been growing exponentially.

According to startup company Deeptrace, there were 7,964 deepfake videos online in early 2019, which nearly doubled to 14,678 nine months later. The number has almost certainly exploded since then.

Now, experts are warning that the problems associated with deepfakes are many-fold.

“In terms of disrupting democratic elections, I think that threat is very real,” said Hany Farid, a digital forensics professor at Dartmouth and one of the world’s leading experts on deepfakes.

The main problem is that any damage done from fake videos is irreversible after they have spread online.

Al Tompkins, a senior faculty member at the Poynter Institute, said “You can’t stuff the genie back in the bottle once the damage is done, particularly in a political campaign where these things get circulated not just in media, but in social channels and conversations.”

The solution is all the more unclear. In 2019, California passed a law making it illegal to create or distribute political deepfakes within 60 days of an election. However, the law could face constitutional questions because the first amendment guarantees freedom of expression. Even beyond that, laws on internet activity are difficult to enforce.

In addition to elections, the Department of Homeland Security has identified risks such as cyberbullying, blackmail, stock manipulation, and international instability.

“If we can’t believe the videos, the audios, the images, the information that is gleaned. Around the world, that is a serious national security risk,” said Farid.

The issue is not just that deepfakes could manufacture events and statements that never happened, but also that anything could be plausibly denied, erasing the line between what is real and what is not. There could similarly be problems for courts if fake information were to be presented as evidence. It’s also possible that cases such as the Vallas incident could be considered defamatory.

Ironically enough, artificial intelligence could be part of the solution. There are tools that can help detect if a video is fake with 90% accuracy, according to The Guardian.

Deep Fakes are emerging in industries such as entertainment as modern cinema is increasingly reliant on computer generated imagery. New AI algorithms can be used to swap faces or replace old or deceased actors.

Not only that, but last year, Dutch police were able to solve a cold case from 2003 by using deepfake technology to create a digital avatar of a 13 year-old murder victim, showing some positive applications. Regardless, the U.S. government is investing millions of dollars into figuring out how to detect deep fakes and the role of social media in promoting this content.

As the technology progresses forward, many agree that something needs to be done to combat this growing problem before it’s too late.