Medical community afflicted by anti-Black racism

Historic discrimination within healthcare system persists decades since segregation

The 2022 Black History Month theme considers activities, rituals, and initiatives that Black communities have done to be well

The theme for this year’s Black History Month is health and wellness, which encourages exploration of the legacy of Black medical practitioners and discrimination within the healthcare system.

Health and wellness has always posed an issue within the Black community; disproportionate access to health insurance, deficient treatment, implicit bias, and other medical disparities have plagued the healthcare industry when it comes to non-white Americans.

The media’s fetishization of violence against Black people, combined with increasing coverage of racially-motivated murders such as that of George Floyd, has resulted in rapidly increasing depression, anxiety, and suicide rates especially among Black youth.

As of 2017, an estimated 10.6 percent of Black Americans were uninsured, according to the Center for American Progress. This figure significantly decreased after the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, which provided coverage for around 2.8 million African Americans according to the Century Foundation. Comparatively, only 5.4 percent of white Americans are not insured.

Yet for the Black Americans who are insured, they are not guaranteed proper care. Implicit bias of medical professionals has led to insufficient treatment for both mental and physical needs.

African American women, for example, are three times more likely to die of pregnancy related complications, according to a report from the CDC. The pregnancy- related mortality ratio, or pregnancy- related deaths per 100,000 live births, was approximately four to five times higher for Black women above the age of 30, compared to white women.

This gap is fueled by ongoing racial stereotypes surrounding Black women, specifically the false claim that they have a nonexistent pain tolerance. In fact, a shocking 2016 study conducted at the University of Virginia found that nearly half of first and second year medical students believed that Black people geneticaly had thicker skin, and thus felt less pain.

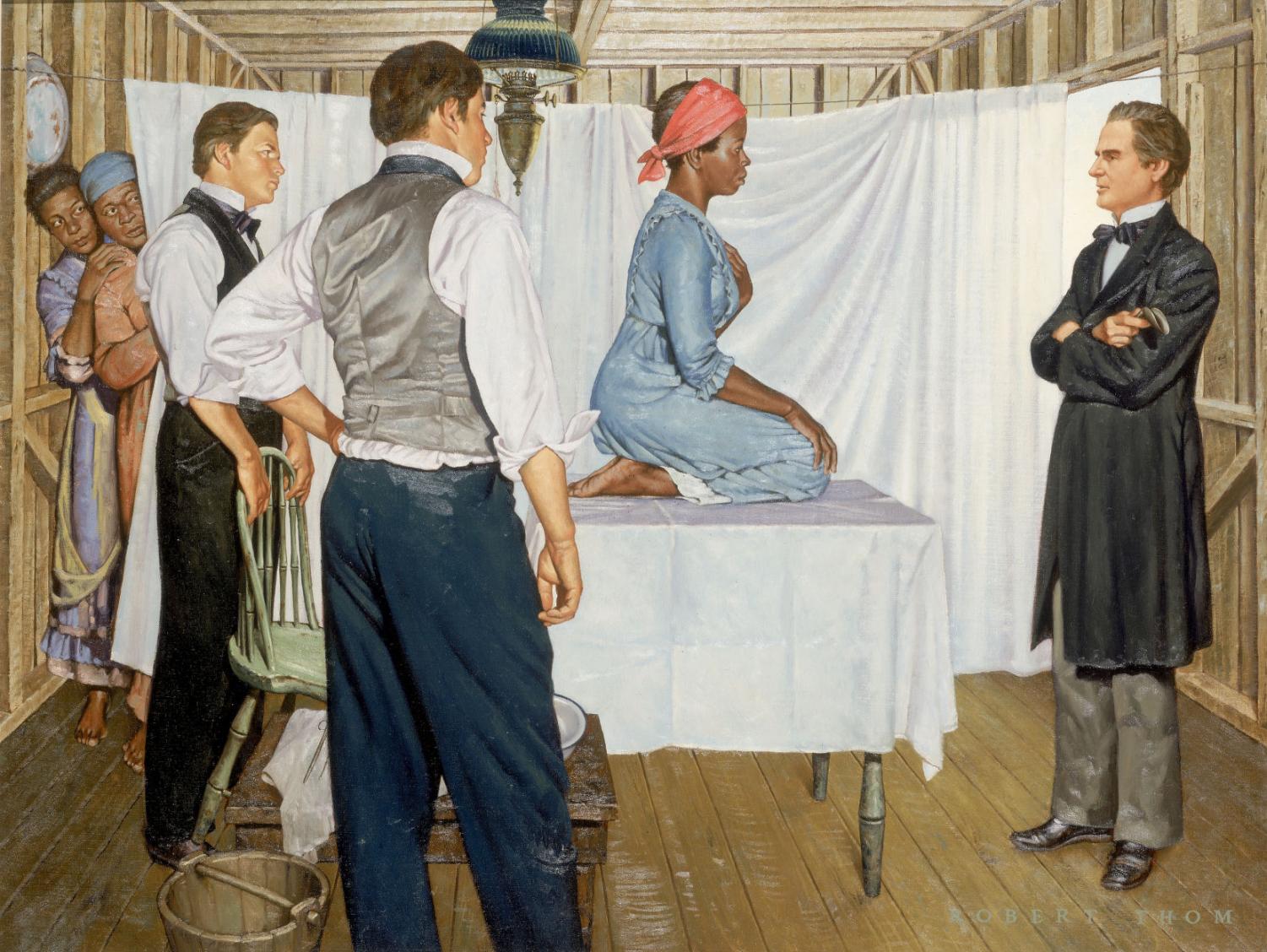

These beliefs have dated back centuries, with doctors such as Thomas Hamilton and James Marion Sims, the credited founder of modern gynecology, who both performed torturous experiments on Black slaves. Sims’ work specifically, which was performed without any anesthesia, established a pool of findings that misrepresented the pain tolerance of Black women.

Due to these racial stereotypes, the pain of Black folk is often under-treated.

Data analyzed by the American Journal of Emergency Medicine revealed that Black patients were 40 percent less likely to receive pain medication for acute treatment than their white counterparts.

The historical racism within the medical community has led to exacerbation of life-threatening conditions as well.

The leading cause of death for African Americans include heart disease and cancer. Black people have both the highest mortality rate for all forms of cancer, and the highest infant mortality rate in general.

Implicit bias has also disrupted the process of receiving mental health treatment for Black Americans.

The MHA, or Mental Health America Organization, states that in 2018, 50 percent of African Americans that needed mental health care did not get any treatment.

The media’s fetishization of violence against Black people, combined with increasing coverage of racially-motivated murders such as that of George Floyd, has resulted in rapidly increasing depression, anxiety, and suicide rates especially among Black youth.

In the months following the death of George Floyd particularly, a CDC survey reported that 15 percent of Black respondents had “seriously considered” suicide.

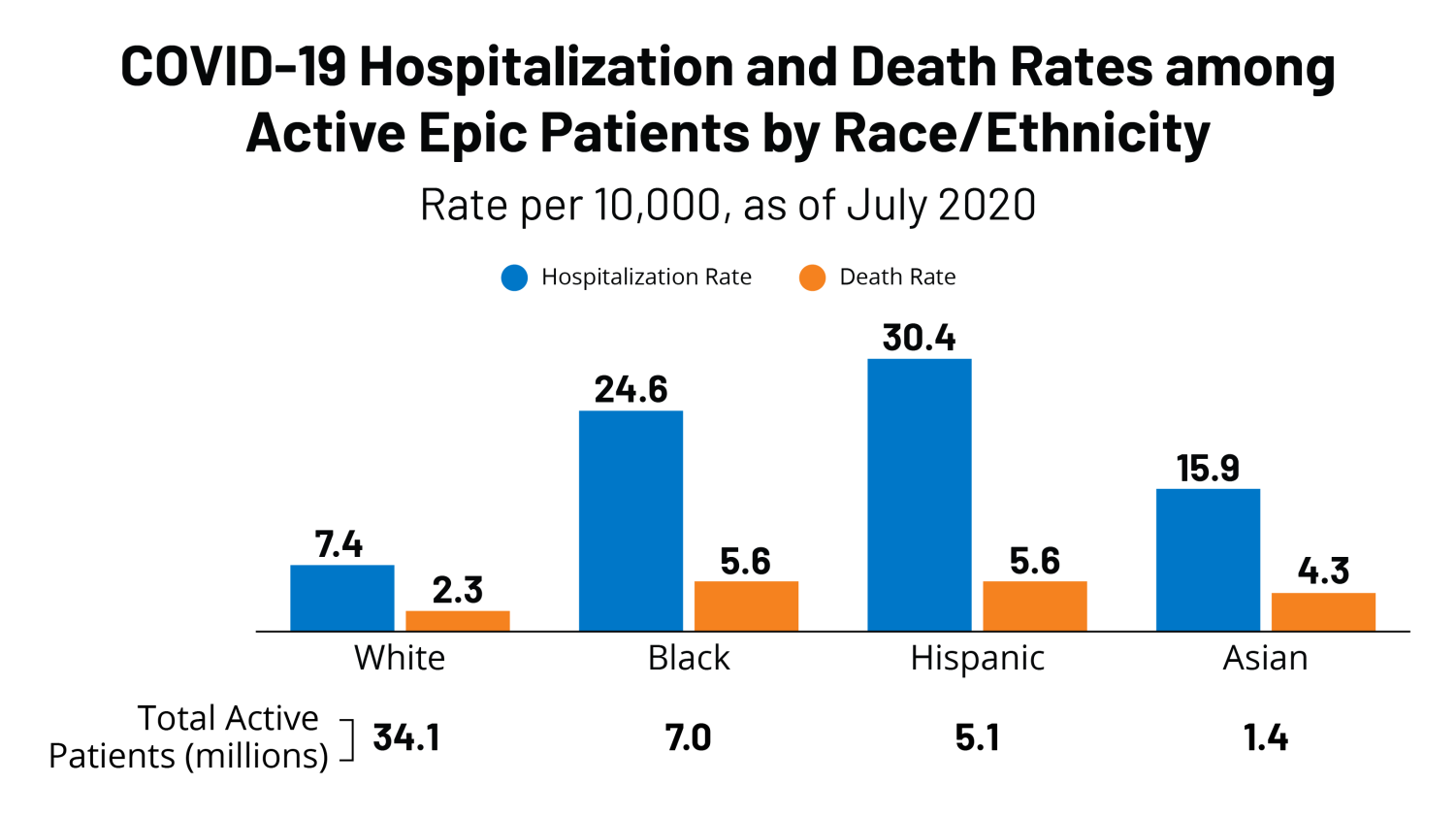

The pandemic has also hit Black communities especially hard, with a disproportionate figure of over 500,000 African Americans dying from the virus. The accumulating effects of systemic racism, such as a lack of generational wealth and available resources, has made predominately communities of color especially vulnerable to the stress of the pandemic.

The problem is expounded by vaccine inequity and inadequate access to hospital beds, which have both played a role in the racial injustice of the pandemic.

As a result of racism within the healthcare system, medical mistrust has risen among Black Americans. With America’s inability to properly care for countless Black lives, the Black community has focused their resources towards fostering mutual aid and social support initiatives. By constructing hospitals and medical schools, one example famously being the Howard University School of Medicine, Black Americans have worked to strengthen their livelihood and combat the discrimination found at many state-sanctioned institutions.

Social justice groups and other grassroot organizations, such as the African Union Society, National Association of Colored Women, and the Black Panther Party, have also aided in the creation of clinics.

Health-centered institutions created by the Black community have increased diversity among practitioners and increased the average life expectancy of African Americans, however there is still much work to be done.

As of 2018, an estimated 5 percent of physicians identify as Black, according to a UCLA study. That figure has risen only 4 percent over the past 120 years; in 1900, only 1.2 percent of physicians were Black.

Despite these numbers, African American medical pioneers contributed great advancements to the health field.

Some of the important Black practitioners that can be recognized throughout history include Dr. Rebecca Crumpler, the first female African American doctor of 1864, who treated freed slaves after the civil war and wrote one of the first medical texts published by a Black American.

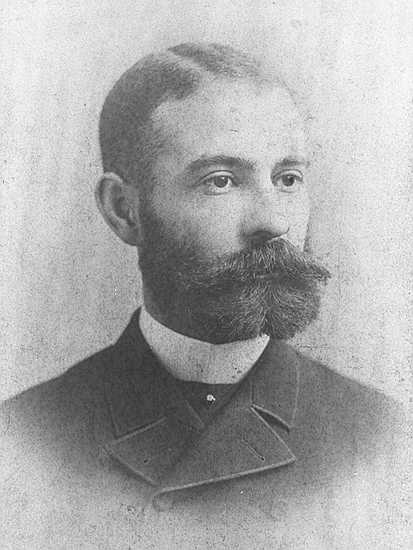

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, another Black MD, not only opened Provident Hospital, the first Black-owned interracial hospital, but also performed the first documented successful open-heart surgery during the summer of 1893. Williams is now regarded as the first African American cardiologist.

As we look upon the legacy of Black doctors during Black History Month, we are reminded of the ongoing need for equitable treatment. These lessons are necessary as we work toward constructing a medical system that ensures the safety and wellbeing of all people.