Juniors complete mandatory state science test

Juniors spent afternoon of early release day taking Illinois Science Assessment

On March 11, juniors spent several hours taking the Illinois Science Assessment, a yearly exam to test scientific skills and knowledge

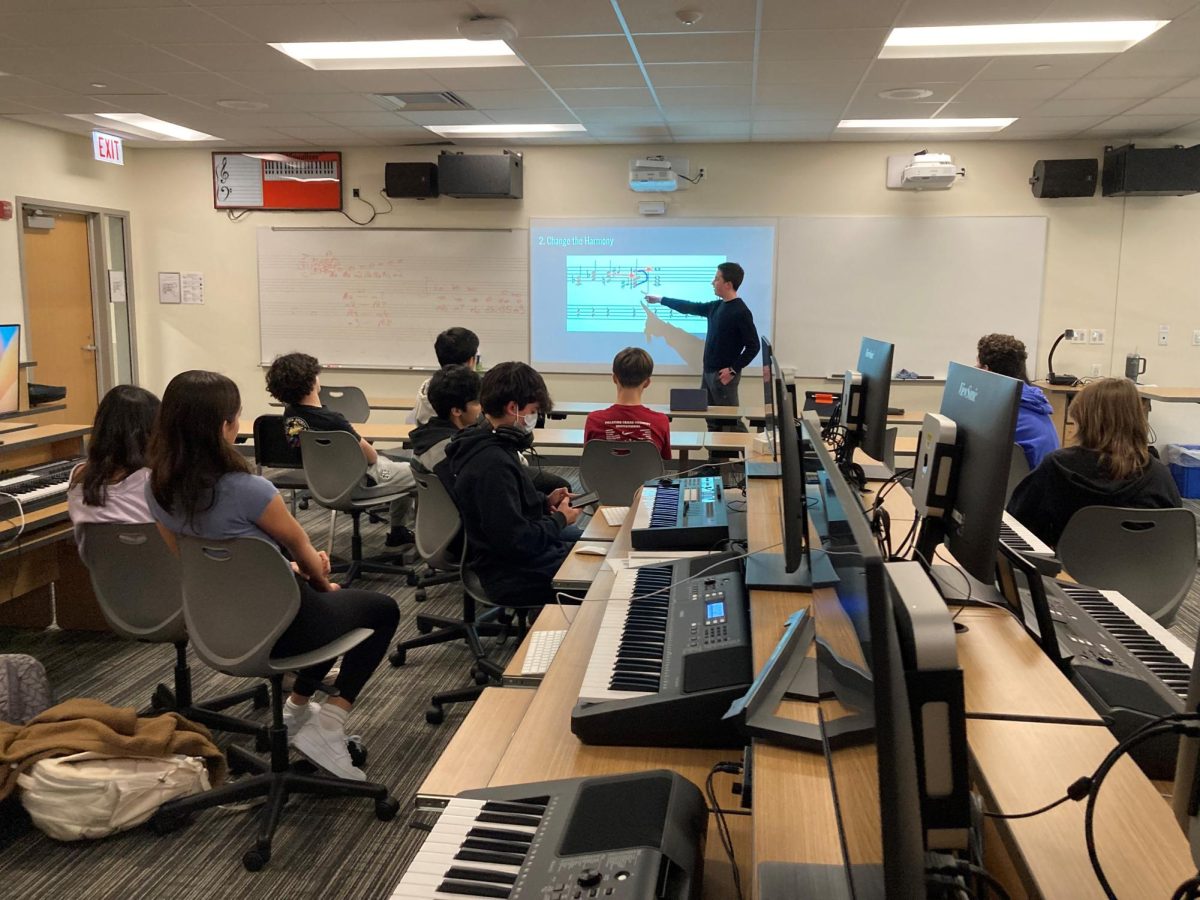

Despite a majority of students leaving to start their weekend three hours early on March 11, juniors were kept through the end of a typical school day for the state science test. Covering biology, geoscience, and physical science, the assessment is meant to reflect three years of learning across the sciences.

If the scores come back from the Illinois Science Assessment and say New Trier students don’t know a particular area of science, as a school, we would need to address student learning gaps.

— Jason English

But for students, there was little incentive to succeed, nor was there a consequence for failure. While this relieved the pressure of needing to study, for students like junior Tisya Kumar, spending hours of the extended weekend on the test seemed unproductive.

“It was kind of exhausting after school to do it even though it doesn’t really affect anything,” says Kumar. “So I feel like it’s kind of pointless, and I don’t totally understand why we did it.”

Whereas the environment around most tests is one full of stress and anxiety, this was far more laid back, and even boring to some. Junior Katarina Teasdale described how no one was happy to be there.

“I think we just wanted to get it over with, so did our proctor,” says Teasdale.

However, the state science test does makes an impact. State funding is allocated differently depending on the school’s test scores, and the state may intervene if test scores are constantly low.

The school also looks at and reflects on these scores, a task headed by Science Department Chair Jason English. He said that although New Trier has never had to and never expects to deal with unexpectedly low scores, it could mean certain funding is taken away, or a new principal (or group of assistant principals) could be hired by the state.

“If the scores come back from the Illinois Science Assessment and say New Trier students don’t know a particular area of science,” says English, “as a school, we would need to address student learning gaps.”

The test is exclusively science because it’s the only state-required core subject that the SAT doesn’t cover. As of several years ago, there was no state science test, but once the SAT was adopted in the 2016-17 school year instead of the ACT, it became a requirement.

Creating and administering the tests has been an evolving process. Parts have been borrowed from other states’ exams, and it was initially only for students enrolled in biology rather than juniors.

“For a while in Illinois, maybe a year or two, the state didn’t test high school students in science,” says English. “The federal government told the state of Illinois that they risked losing federal funding associated with the No Child Left Behind Act if they didn’t test students in science.’”

New Trier rarely has to face consequences like reevaluating their teaching from the state because of low test scores. Even as new tests are introduced, or old ones are edited, teachers and administrators expect students to perform well.

Data from the 2020 and 2021 testing has not yet been scored by the state, but the Illinois Report Card showed in 2019, New Trier students were “proficient” in the tests at a 75% rate, compared to only a 49% rate for the rest of Illinois. Scoring from New Trier has generally been consistent with the rest of the district, who saw 79% of their tests scored as proficient.

Coming out of the assessment, students felt like it was very manageable. This differed for each student, as one who hasn’t taken biology would likely struggle more in that section, but in general, many felt well prepared.

“For example, if you haven’t taken physics, then you’re not going to know that it would have moved left for however many feet,” says Teasdale. “But if you did take it, or the other subjects, this exam was pretty good.”

While the test had no effect on the individual student, so there may have been little motivation for success, it remains impactful in how the school continues to teach science.

“While your scores may not go with you as an individual, your scores certainly help the school,” says English. “It does make an impact because we want our school to be in the best position possible for student learning success.”

![Seniors Mia Moline [on the floor] and Elizabeth Feoktistov [right] test their bridge for the build event in Solon, Ohios Invitationals on January 15](https://newtriernews.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IMG-2941-475x267.jpg)